Parashat D’varim Study Guide Themes

Theme 1: Retelling History at the Threshold of the Promised Land

Theme 2: Ties That Bind: Dealing Peacefully with the Kinfolk on the Way to the Promised Land

Introduction

The first parashah in the book of Deuteronomy takes place in the lower Jordan valley at the plains of Moab, on the east side of the Jordan River. At last, the Israelites are ready to enter the Promised Land. Parashat D’varim begins with the first of Moses’ farewell addresses to the people. Rather than an objective review of the facts of Israel’s history, Moses’ words emphasize the primary theological and ideological themes that will be woven throughout Deuteronomy. There is a twofold audience for Moses’ remarks. The first audience is the Israelites in the biblical narrative who stand on the threshold of the Promised Land. They can either repeat the mistakes of the prior generation or make different—and better—choices if they follow God’s commands. The second intended audience is the contemporaries of the authors of Deuteronomy. Most scholars date the material in Parashat D’varim to the period of the Babylonian exile (586– 538 B.C.E.), believing that it was written as an introduction to the laws that follow later in Deuteronomy. The exiles will need Deuteronomy’s laws once they return to Eretz Yisrael and begin to rebuild their lives. Because Moses’ remarks are directed to an audience soon to return from exile, the biblical authors emphasize God’s role in Israel’s history, the theological justification for Israel’s possession of the land, and obedience to God as the keys to Israel’s success both politically and militarily.

Before Getting Started

Before turning to the biblical text and the questions presented below, use the introductory material in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary to provide an overview of the parashah as a whole. Draw attention to a few key quotations from the 2 introduction to the Central Commentary on pages 1039–40 and/or survey the outline on page 1040. This will help you highlight some of the main themes in this parashah and give participants a context for the sections they will study within the larger portion. Also, remember that when the study guide asks you to read biblical text, take the time to examine the associated comments in the Central Commentary. This will help you answer questions and gain a deeper understanding of the biblical text.

Theme 1: Retelling History at the Threshold of the Promised Land

Moses’ first farewell speech begins with a retelling of Israelite history. Moses juxtaposes places linked with the Israelites’ disobedience to God—and the resulting consequences of this disobedience—with places where the Israelites followed God’s commands and enjoyed success on their journey toward Canaan. Moses’ remarks emphasize God’s faithfulness to the promises made to the Israelites, despite their chronic misbehavior. The people will require new leaders so that they do not repeat the mistakes of the past. These leaders must possess the requisite characteristics for the upcoming military campaign and the settlement of the Promised Land. These leaders will guide the people, and God will be with them.

- Read Deuteronomy 1:1–5, in which Moses sets the tone for his first farewell address to the Israelites.

- According to verse 1, where and when does Moses speak these words to the Israelites? According to the Central Commentary, what can we learn from the phrase “on the other side of the Jordan” (v. 1) about the intended audience for Moses’ words? According to verses 3–5, where and when does Moses speak these words? How does this differ from the place and time that Moses delivers his address according to verse 1?

- In your view, how can we reconcile the difference between verse 1, which states that Moses speaks “these words” at various places during Israel’s wilderness journey, and verses 3–5, which state that Moses speaks “this Teaching” at the end of the journey, as the Israelites stand on the plains of Moab? How does the setting of Moses’ address “in the fortieth year” (v. 3) help you to understand this difference?

- Verse 1 lists the various locations at which Moses addresses the Israelites. The Israelites doubted God’s saving power at Suph and complained about wanting meat at Paran. Miriam and Aaron spoke against Moses at Hazeroth. In your view, why does the text mention these places at this point? What do we learn by comparing the events described in verse 4 and those that occurred at Suph (Exodus 14:10–12), Paran (Numbers 11), and Hazeroth (Numbers 12:1–2)?

- The phrase “expound this Teaching” in Deuteronomy 1:5 uses a form 3 of the verb yod-alef-lamed (translated here as “undertook”), which has the sense of beginning a new initiative. The verb bei-eir that follows (translated here as “expound”) can also mean “to elucidate or annotate.” How does this help you to understand the purpose of Moses’ address?

- Read Deuteronomy 1:9–17, which describes the appointment of tribal leaders.

- What is the reason Moses gives in verses 9–10 for appointing tribal leaders? How does this contrast with the reason Moses gives in verse 12? How does the juxtaposition of these reasons reinforce the contrasting themes of God’s loyalty to previous promises and the Israelites’ chronic misbehavior?

- According to verse 13, what are the qualities the tribal leaders should possess and who should appoint them? In Numbers 11:16–20, God instructs Moses to gather seventy elders to help govern the people. God imbues these leaders with Moses’ spirit. In your view, what do the differences between the Deuteronomy and Numbers texts suggest about the kind of leadership needed as the Israelites enter the Promised Land?

- Read Deuteronomy 1:19–33, which retells the story of the reconnaissance mission of the Promised Land by twelve scouts (see Numbers 13–14).

- In your view, what is the underlying message of Moses’ words to the people in Deuteronomy 1:20–21?

- The root y-r-sh of the word reish in verse 21, translated here as “take possession,” can also mean “to take possession by force” or “to inherit.” How do these varying meanings suggest the complicated nature of the Israelites’ acquisition of the territories that are designated as the Promised Land?

- According to verses 22–23, who gives the order to send the scouts? How does this differ from the initial episode in Numbers 13:2? What do you think accounts for the change in the retelling?

- How does the scouts’ description of the Promised Land in Deuteronomy 1:25 contrast with their report in Numbers 13:27–29? What do the differences between these versions of the scouts’ description of the Promised Land tell us about the agenda of the Deuteronomy text?

- In Deuteronomy 1:26–28, Moses describes the Israelites’ reasons for refusing to enter the Promised Land. What message does Moses convey to the people in verses 29–33? What is the view of the prior generation in these verses?

- What image of God does verse 31 present? According to the Central Commentary, what do we know about who cared for children in ancient Israel? How does the image of God in this verse compare with that of God in Numbers 11:12?

- Read the Another View section by Tammi J. Schneider (p. 1056).

- According to Schneider, how does the word ho-il (translated as “undertook” in Deuteronomy 1:5) suggest that Moses is engaging in the time-honored Jewish tradition of reinterpretation of text? How is Moses’ retelling of these events a commentary on the Torah itself?

- In your view, why does Moses’ retelling of prior events put more power in the hands of the people for choosing judges (Deuteronomy 1:13 versus Exodus 18:25) or sending out scouts (Deuteronomy 1:22 versus Numbers 13:1)?

- What does parashat D’varim teach us about how traditions change over time, even within the Torah? How is this lesson particularly relevant for women and liberal Jews?

- Read the Contemporary Reflection by Ellen Frankel (pp. 1058–59).

- What is the impact of the repeated use by Moses of the word “you” in the book of Deuteronomy?

- According to Frankel, how does Moses’ first farewell speech reflect his own unresolved conflicts about what has transpired between him and the people over the preceding forty years?

- In what ways is Moses’ retelling of history and his chastisement of the people an attempt to rewrite his own life story? Can you think of a time when someone in your life retold her or his own life story? What motivated the retelling? To what extent did the retelling differ from the original events? How did you react to this retelling?

- According to Frankel, how is the Moses of parashat D’varim like the parent of the rasha in the Passover seder?

- If you are a parent, can you think of times when your children were on the verge of a major change in their lives and asserted their autonomy? How did you feel at these times? If you felt rejected, how did you understand those feelings?

- Read the excerpt from “The Generations Upon Me” by Barbara Reisner, in Voices (p. 1060).

- How does the poet connect her walk through “the tired city” with her grandmother?

- We learn that the poet’s grandmother brought a copy of the book of Deuteronomy with her to America. What haunts the poet about the image of her grandmother reading “These are the words”?

- How does the poet contrast her own actions with Moses’ command to “start out and make your way” (Deuteronomy 1:7)?

- What is the poet’s view, as expressed in the last stanza, of her own role as “a guardian, the generations upon me”?

- How do you see yourself as a guardian of the Jewish tradition that has been given to you? What are the rewards of being a guardian? What are the challenges?

Theme 2: Ties That Bind: Dealing Peacefully with the Kinfolk on the Way to the Promised Land

As the Israelites prepare to enter the Promised Land, Moses recounts the events that transpired over the past forty years. Moses describes how the Israelites encountered five nations in the area currently known as Transjordan. In the first three of these encounters, God commands the Israelites to deal peacefully with Edom, Moab, and Ammon because they are Israel’s kin. The text emphasizes the importance of honoring the rights of kin who are also the recipients of divinely granted territory. Moses confronts a potential conflict with kinfolk in a different way when the tribes of Gad and Reuben wish to remain with their families on the east side of the Jordan. The repetition of phrases related to God’s giving of the land and the Israelites’ taking possession of the land emphasizes that while the Edomites, the Moabites, and the Ammonites are their kin, God’s relationship with the Israelites is unique.

- Read Deuteronomy 2:2–7, which describes God’s commands to the Israelites regarding the Edomites.

- How are the residents of Edom identified in verse 4? According to the Central Commentary to this verse, what does the concept of “kin” signify in the book of Deuteronomy? To what rights are Israelite kin entitled?

- In your view, what is the significance of mentioning Esau in verse 4–5?

- How are the Israelites commanded to treat the Edomites as they pass through their territory (vv. 6–7)? What is the relationship between these commands and the concept of kin in verse 4?

- Of what does God remind the people in verse 7? In your view, why is this reminder necessary?

- Read Deuteronomy 2:9–13, which describes the Israelites’ encounter with Moab.

- How does the territory of Moab derive its name (see Genesis 19:30–38)?

- How does the Genesis narrative of the origins of the Moabites help you to understand the Israelites’ complicated relationship with this tribe?

- In what way does the story of Ruth reveal an additional facet of the complicated relationship between Israel and Moab?

- Read Deuteronomy 2:16–19, which describes the Israelites’ encounters with Ammon.

- How does the encounter with Ammon parallel that with Moab (vv. 2–7)?

- From what does the territory of Ammon take its name (see Genesis 19:38)? How does this link the Ammonites to Abraham?

- What rights do the Ammonites have, according to verse 19? What is the relationship between these rights and the origins of the Ammonites?

- Read Deuteronomy 3:12–22, which describes Moses’ allotment of land east of the Jordan.

- What is the reason that the tribes of Reuben and Gad ask to take possession of land east of the Jordan instead of settling in the Promised Land? In your view, with what challenge does this present Moses?

- Why do you think Moses commands the men of Reuben, Gad, and Manasseh to join the rest of the Israelite forces when they invade and conquer the Promised Land?

- The verbal root n-t-n (translated as “I am giving,” “I assigned,” “has given”) occurs repeatedly in these verses, with God as the subject. What does the repetition of this root demonstrate to you about the Israelites’ possession of the land of Canaan and the lands across the Jordan?

- Likewise, the word “land” occurs repeatedly in these verses, as does the word translated as “take possession.” How does the repeated use of these words emphasize God’s role in the Israelites’ possession of these lands?

- How does Moses’ charge to Joshua (vv. 21–22) frame the Israelites’ military victories? What is the relationship in these verses between God and the Israelites’ military victories? How does this relationship help you to understand the emphasis in this parashah on respecting the boundaries delineated by God and God’s promise of the land to the Israelites?

- What two reasons are given for God’s command to behave peaceably toward Edom, Moab, and Ammon (see 2:4–5, 2:9, 2:19)? What do these reasons, along with God’s specific instructions, add to your understanding of the people’s conquest of the Promised Land?

- Read “Move” by Alicia Suskin Ostriker, in Voices (p. 1061).

- What is the comparison the poet makes between humans and the turtle and the salmon? Why does the poet think humans are envious of the turtle and the salmon? In your view, what role does envy play in our understanding of those who are outside of our “tribe” and in our relationships with those who are outside of our “tribe”?

- In your view, what is the relationship between the humans and the nonhuman characters in the poem? What are the similarities between the two, and what are the differences? What impact do the characters have on each other?

- In the poem’s eighth and ninth stanzas, how does the poet compare human “travels” to those of the turtle and the salmon?

- How does the poet contrast the salmon’s and the turtle’s laying of their eggs (“nowhere else in the world”) with how humans say they will “know we are in the right spot”?

- How does the poet’s use of the phrase “our tribe” in the poem’s eighth stanza help you to understand the significance of the tribes in this parashah?

- What is the relationship between the way this parashah portrays the Israelites’ journey to the Promised Land and the turtle and the salmon’s “absolute right choice”? Can you think of a situation in your own life where the importance of the destination outweighed the value of the journey?

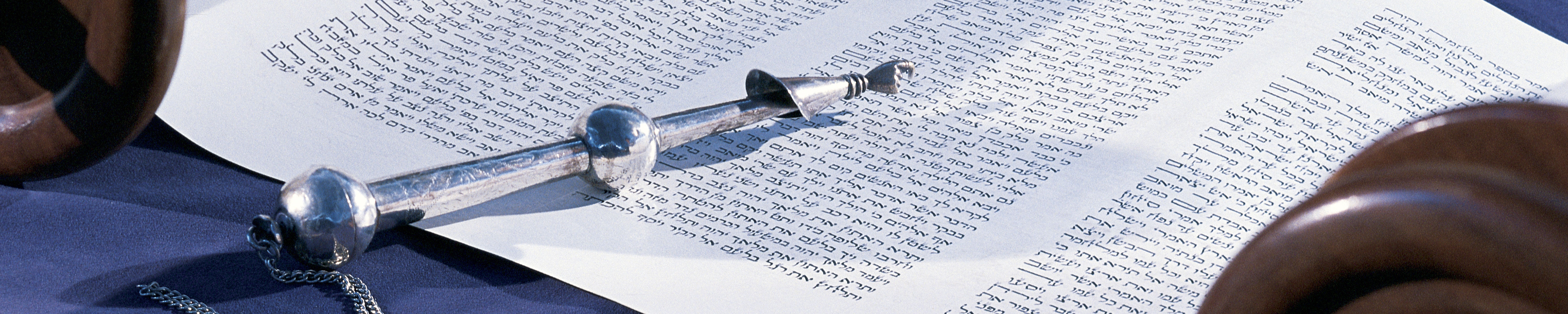

- Read “They’ve Rolled the Parchment” by Shirley Kaufman, in Voices (p. 1062).

- To what does the poet refer in the first three lines of the poem?

- How does the situation described by the poet change as the poem continues?

- How does the poet imagine the benefits of a “shorter way through the wilderness”? In her view, how might a shorter way have changed the journey?

- What associations do you have with the layout of this poem? Why do you think the poet formatted the poem in this manner?

- What is the relationship between the poet’s own journey and the way she strips herself “of the past year”?

- In your experience, how can “the hum of prayer” be as “warm as an old sweater”?

- How does the poet imagine the Israelites’ encounters with various tribes on the journey through the wilderness? What would have been lost without these encounters? In this parashah, how do the Israelites benefit from their encounters with their kin the Moabites, the Edomites, and the Ammonites?

- In your view, in what ways did the Israelites benefit from their long journey through the wilderness?

- How have you benefited in your life from a journey that was longer, rather than shorter?

- In what ways has your life been shaped by your associations with relatives outside of your immediate family?

Overarching Questions

As you study these parts of the parashah, keep in mind the following overarching questions. If time permits, conclude the class with these broader questions:

1. If you are involved in choosing leaders in a professional or volunteer organization, what can Parashat D’varim teach you about the qualities necessary for successful leadership? How can this parashah help us to better evaluate and select leaders suited to particular tasks and times in the life of an organization?

2. In Parashat D’varim, God commands the Israelites to deal peacefully with the kin whose lands they will cross on the way to the Promised Land. God provides not only instructions but a rationale for why the Israelites must deal peacefully with these nations. Can you think of a situation in your own extended family in which a potentially adversarial or difficult situation was resolved peacefully? What led to this resolution? What can we learn from Parashat D’varim about how we can resolve such potential conflicts?

Closing Questions

1. What new insight into the Torah did you gain from today’s study?

2. What other new insights did you gain from this study?

3. What questions remain?