Parashat Mishpatim Study Guide Themes

Theme 1: Women under the influence (of Men)

1a.Women as indentured Servants

1b. Women as Victims of Crime

Theme 2: Women under the influence (of God): Miscarriage and infertility

INTRODUCTION

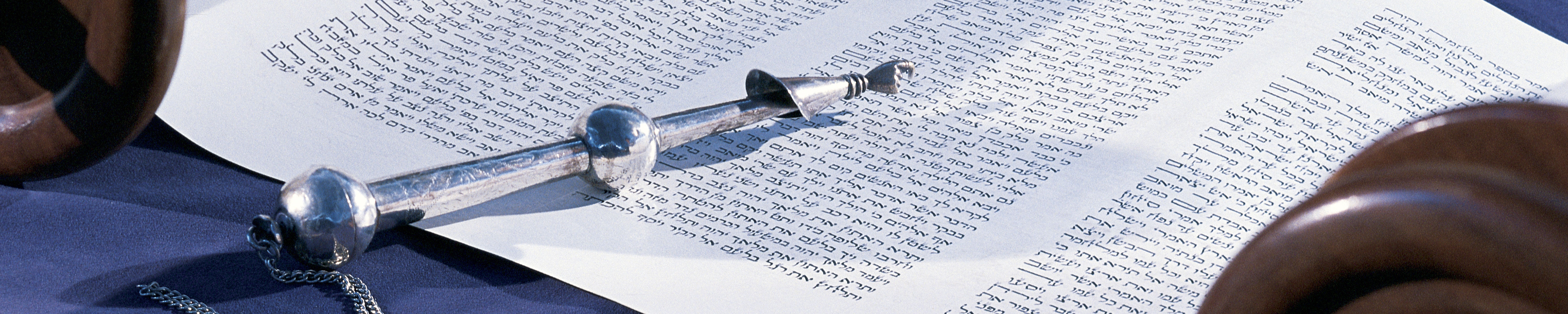

In the previous parashah, Yitro, the covenantal relationship between God and the Jewish people begins with the giving of the Ten Commandments. These basic principles guide and structure the relationship between the Israelite community and their God, and between and among the people themselves. Here, in Parashat Mishpatim, we find a more specific and detailed collection of civil and religious regulations concerning indentured servitude, assault, damages for bodily injury and death, treatment of foreigners and other vulnerable individuals, and festival observances. In some of the situations detailed in this portion, men and women are to be treated similarly (see Exodus 21:20); in others, significant gender differences are stipulated (see Exodus 21:7). In these regulations, the reader can discern an effort to regulate and control the human passions that are often aroused when loss or significant injury—whether to property or people—occurs. Thus this collection of stipulations can be seen as an attempt to maintain communal cohesiveness and prevent disorganization, breakdown, and disintegration of the group. However, these laws do not attempt to legislate an idealized—and unsustainable—community structure. For instance, although the Israelites have recently been liberated from Egyptian oppression, there is no attempt in this code of laws to outlaw indentured servitude. Rather, this legislation acknowledges and works within the reality of the human need for hierarchies of power and status. Overarching all is the clear message that the people’s well-being is utterly dependent on their adherence to this God-given set of injunctions. God will reward and God will punish according to the Israelites’ own actions.

This study guide will highlight two themes. In the first, “Women under the influence (of Men),” participants will study the particular situations of women as indentured servants and as victims of crime. the second, “Women under the influence (of God),” considers the cause and consequences of infertility and miscarriage in biblical times.

BEFORE GETTING STARTED

Before turning to the biblical text and the questions presented below, use the introductory material in the Torah: A Women’s Commentary to provide an overview of the parashah as a whole. Draw attention to a few key quotations from the introduction to the Central Commentary on pages 427–28 and/or survey the outline on page 428. This will allow you to highlight some of the main themes in this portion and give participants a context for the sections they will study within the larger parashah. Also, remember that when the study guide asks you to read the biblical text, take the time to examine the associated material in the Central Commentary. This will help you to answer questions and gain a deeper understanding of the biblical text.

THEME 1: WOMEN UNDER THE INFLUENCE (OF MEN)

1a. WOMEN AS INDENTURED SERVANTS

- Read Exodus 21:1–11.

- According to Elaine Goodfriend, what constituted “slavery” in Israelite society? How did this form of servitude differ from those described in other ancient Near Eastern law codes? Look back at the Central Commentary to Exodus 1:11 (p. 308). What was Egyptian corvée labor, and how did it compare to indentured service or debt-slavery?

- Verses 2–6 describe the choices available to a freed Hebrew slave who married and fathered children while in servitude. What was the status of the children of such a union? Why do you think freed Hebrew slaves were presented with the two options described here? Why were these two options their only choices? How would these arrangements have benefited the master? How might these arrangements have benefited the freed slave? What would the impact of these arrangements have been on the servant’s wife and family?

- Goodfriend notes that the servant discussed in verse 2 could be either a male or female servant. this type of servant, called an eved in the text, was to be released at the end of six years (p. 430). However, this rule did not apply to the indentured daughter, referred to by the term amah in verse 7. In the latter case, Goodfriend writes that “marriage to the master or the master’s son seems to be the condition the father makes for the daughter’s indenture” (p. 431). How does Goodfriend explain different ways that a woman could have become a servant? What do you think might account for the difference in the treatment of a male or female servant as opposed to an indentured daughter?

- Verses 7–11 touch on sexual rights and obligations of both males and females. According to Goodfriend, who could sell a daughter into debt-slavery? Under what circumstances might this happen? What type of relationship does this passage presume between master and servant? Under what circumstances might such a daughter obtain her freedom?

- Read Goodfriend’s explanation of the phrase “displeasing,” which she translates more literally as “bad in the eyes of her master” (v. 8). Do you agree with the interpretation of this phrase given by some commentators? Why or why not? What else might this phrase mean?

- What are the three provisions that a master had to make for an indentured female slave (v. 10)? According to Goodfriend, what are some of the possible meanings of the third provision (onah)?

- Goodfriend explains that “her food, her clothing, or her conjugal rights . . . comprise the basic entitlements of a married woman” (p. 432). How does this list compare to your understanding of “basic entitlements” in the contemporary marital relationship?

- Read the post-biblical interpretations in which Susan Marks explains some of the differences between servitude in biblical and post-biblical society (pp. 445–46). What were the protections afforded female slaves in the biblical period that were not applied later? In the post-biblical period, how did the sexual availability of female slaves both benefit and harm the males in their masters’ households? Since freed female slaves were presumed to no longer be virgins, how did this understanding impact the freed women’s lives upon emancipation?

- In Post-biblical interpretations, Marks writes, “Although the liberation story of Exodus was always a central focus of Judaism, few commentators have struggled with the larger issues of enslavement that continued for centuries in Jewish societies” (p. 446). Why do you think these “larger issues” were rarely questioned? What relevance does this theme still hold in today’s world?

- In her Contemporary Reflection (pp. 447–48), Rachel Adler explains that the slave woman in exodus 21:5–6 is a non-Israelite, probably a foreign woman in bondage. For this woman, how would her fertility or barrenness impact her status with her master, perhaps even her very life? According to Adler, what were the foreign bondswoman’s options? What might have been her greatest asset? Her greatest deficit? What do you think was her area of greatest vulnerability? What does Adler’s essay add to your understanding of the biblical text?

1b. WOMEN AS VICTIMS OF CRIME

- Read Exodus 21:18–32.

- According to Goodfriend (see p. 429), what is the Covenant Collection? What is its “distinctive feature”? Why would the placement of Exodus 21 immediately after the decalogue (“Ten Commandments”; Exodus 20:1–14) have led to the inclusion of women as equally entitled to legislative protection?

- Exodus 21:22 describes a scenario in which “a miscarriage results, but no other damage ensues.” According to Goodfriend, what are the interpretive possibilities for the Hebrew word ason? How do the two scenarios involving “damage” that are presented here differ? What does the Torah text understand the “damage” of miscarriage to be? How might the talion principle explained in the note to verse 24 clarify your understanding of this passage? From whose viewpoint might this description have been written?

- In the Torah text, to whom is the fine for miscarriage to be paid? Who negotiates this penalty? In this situation, what is the role of the woman who has miscarried? Why do you think the compensation in this situation is in monetary form?

- According to Goodfriend (see p. 434), what is the distinction made in Jewish law between the life and value of the fetus and the life and value of the mother? What does it say about the biblical perspective on life?

- Verses 26–27 describe the obligation incumbent on a slave owner who causes bodily damage to a male or female slave. Why do you think that here the Torah text explicitly includes both genders, referring to “a slave, male or female”? In her note to verse 20, Goodfriend points out that the Covenant Collection makes gender-inclusivity explicit in eight of its first laws. Find some of the other places in this parashah in which both men and women are mentioned (see p. 427). What are the issues? Why do you think these passages specifically mention both men and women? What implications might we draw from this?

- In Post-biblical interpretations (p. 446), Marks explains the difference between the Torah’s understanding of the term “other damage” with that found in the third-century Greek translation of the Bible. What are these two interpretations of “other damage”? How did the Rabbis later use the Hebrew text to formulate penalties for fetal and maternal deaths? Do you agree with their application of nefesh, legal human life, to the mother but not the fetus?

- Read Vicki Hollander, “After a Miscarriage: Hold Me Now,” in Voices (p. 449). How does Hollander understand the “damage” of miscarriage? What forms does “damage” take in this poem? How does the concept of the damage of miscarriage in this poem contrast to the “damage” associated with miscarriage described in the Torah text poem compare to that found in the Another View?

THEME 2: WOMEN UNDER THE INFLUENCE (OF GOD): MISCARRIAGE AND INFERTILITY

Read Exodus 23:20–26.

- In this section, God explains that if the Israelites obey all the instructions given previously in this portion, they will be protected and blessed. Specifically, what is being promised to the Israelite community? Why do you think these rewards were promised? What else would you add to this list?

- Which “blessings” specifically had an impact on the female members of the community? According to Goodfriend, what female needs were met by fertility?

- Do you think that contemporary women are also “protected” by the gift of fertility? If so, in what ways? How has our notion of the “benefits” of fertility changed or expanded since biblical times?

- According to this text, what is the cause of miscarriage and barrenness? Why does this understanding of miscarriage and infertility make sense in the context of the ancient biblical world? What remnants of these beliefs still exist today? How does the biblical understanding of these issues compare to your own perspective?

- There are two statements in verse 26: “No woman in your land shall miscarry or be barren” and “I will let you enjoy the full count of your days.” Read Goodfriend’s comment on this verse (pp. 442–43). What is the connection between these two parts of the verse? What insight does this verse provide into ancient views of women’s role in society? In what way has this changed, and in what way does it still apply today?

- Read “under the Spell of Miscarriage,” by Jessica Greenbaum (p. 449). to whom is the writer speaking? Why does she call the recipient of her poem both “powerful” and “neglected”? Why might “neglect” lead “the one who forbids creation” to retaliate with miscarriage? What does Greenbaum suggest ought to be the proper relationship between “the one” and the writer?

- Read “Barren,” by Rahel on p. 450. Why do you think the woman speaking in the poem longs specifically for a son? What does she imagine this child will bring her? Why does she invoke the names of other biblical women who struggled with infertility, “mother Rahel” and “Hannah at Shiloh”? What might this suggest to the reader about the places of solitude and community when one is confronting life’s most difficult challenges? To what extent can you relate to Rahel’s sense of longing?

Overarching Questions

As you study these parts of the parashah, keep in mind the following overarching questions. if time permits, conclude the class with these broader questions:

- What do you think are some of the factors that motivate people to enslave or bind other human beings into servitude?

- When they have power over other people, do you think there are differences in how women and men use their power? If so, how would you characterize those differences? to what do you attribute these differences?

- Has there been a time in your life when you found yourself in a position of power over other human beings? How did it feel, and what were the challenges of your position? Have you ever been in a relationship or situation in which you felt oppressed or powerless? How did you respond, and what did you do? Looking back at this time from a position of greater life experience, what have you learned, and what might you do differently now?

Closing Questions

- What new insight into the Torah did you gain from today’s study?

- What other new insights did you gain from this study?

- What questions remain?