Parashat P’kudei Study Guide Themes

Theme 1: Giving Credit Where Credit is Due

Theme 2: Completing the Tabernacle “To Do” List

Introduction

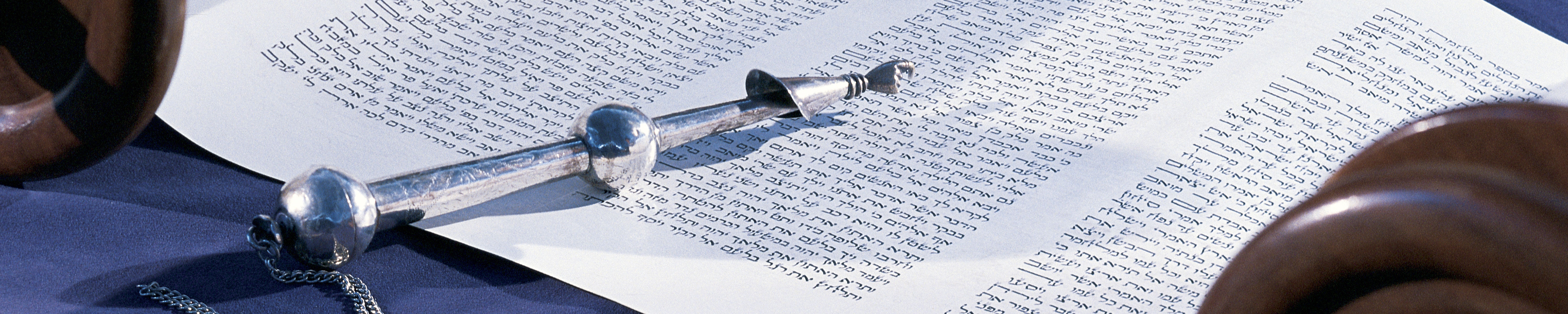

The planning, construction, and completion of the Tabernacle (Mishkan)—the earthly “home” for God—occupy much of the last five parashot in the book of Exodus. Exodus 25–31 are largely prescriptive texts, providing the detailed instructions for constructing the Mishkan and its contents. The subsequent chapters (Exodus 35–40), referred to as descriptive texts, record the execution of these instructions. Parashat P’kudei, which concludes the book of Exodus, describes the completion of the construction process and the dedication of the Tabernacle. The parashah contains a detailed account of the inventory of construction materials and priestly vestments. It reaffirms Moses’ unique relationship with God, especially in its parallels with the creation of the universe (Genesis 1:31–2:3) and its highlighting of Moses as the primary “contractor” of the Mishkan. In this role, Moses must faithfully account for the construction materials as well as complete the final steps necessary for the erection of the Tabernacle. The parashah concludes with the Presence of YHVH filling the Tabernacle, fully visible to the Israelites as they prepare to continue on their journey to the Promised Land.

BEFORE GETTING STARTED

Before turning to the biblical text and the questions presented below, use the introductory material in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary to provide an overview of the parashah as a whole. Draw attention to a few key quotations from the introduction to the Central Commentary on pages 545–46 and/or survey the outline on page 546. This will help you highlight some of the main themes in this parashah and give participants a context for the sections they will study within the larger portion. Also, remember that when the study guide asks you to read biblical text, take the time to examine the associated comments in the Central Commentary. This will help you answer questions and gain a deeper understanding of the biblical text.

THEME 1: GIVING CREDIT WHERE CREDIT IS DUE

The parashah opens with a review of the records connected with the construction of the Tabernacle. The inventory of donated materials and their use in Exodus 38:21–31 is more than a matter of accounting: it is sacred work, a way of ensuring that the Mishkan will be a suitable earthly “home” for God as well as a shelter for the tablets that contain God’s covenant with the Israelites. This inventory reminds the community that their heartfelt, abundant contributions of materials and artistry have made this sacred space a reality. Parashat P’kudei also describes the fashioning of the vestments to be worn by the priests when they conduct rituals in the Tabernacle. Although the text does not specify who made the vestments, other biblical passages and extra-biblical resources suggest that these garments may have been produced by women. Our parashah shines the spotlight on Moses, crediting him with the completion of the Mishkan. The text suggests, however, that without the efforts of others who are not named, the Tabernacle could not have been constructed. In this theme, we will explore how both those who are named and unnamed must be credited with the undertaking of building the Tabernacle, its contents, and the ritual garments necessary for enacting the rites for which the building was made.

- Read Exodus 38:21–23, which presents an inventory of the donated materials.

- The root p-k-d, from which this parashah takes its name, is used twice in Exodus 38:21 (“records” and “were drawn up”). The noun form of this word, which is translated as “records,” can also be translated as “expenses.” The verb, which is translated as “were drawn up,” can also be translated as “were passed in review.” How might substituting these two alternative translations shape your understanding of this verse? What is the effect of the repetition of the same root in one verse?

- Verse 21 uses a unique phrase, “Tabernacle of the Pact.” Elsewhere, this sacred structure is referred to as the “Tabernacle” (e.g., Exodus 25:9), the “Pact” (e.g., 25:16), or the “Tent of Meeting” (e.g., 27:21). According to the Central Commentary by Carol Meyers on 38:21, why is it significant that the words Mishkan (Tabernacle) and edut (Pact) are used together in this verse?

- We read in Exodus 38:21 that the Tabernacle was drawn up “at Moses’ bidding.” The Torah also portrays Moses as prophet, leader, and judge. Why, in your view, is Moses’ role as the one who directs the construction of the Tabernacle emphasized here? How might Moses’ role in this parashah add to your understanding of his other roles in the Torah?

- The phrase “as Adonai had commanded Moses” is repeated fourteen times in this parashah. In Exodus 39:1–31 it is repeated seven times. Why do you think this phrase is repeated so often? What does the repetition suggest about God’s role in the construction of the Tabernacle versus Moses’ role?

- Aaron is mentioned in Exodus 38:21 and 39:1, but not again in the parashah. instead, Moses takes center stage. Read Exodus 32:1–6. How might Aaron’s role in the Golden Calf incident account for his absence in our parashah?

- Read Exodus 39:1 and 39:22–31, which describe the garments worn by the priests who serve in the Tabernacle.

- In these verses we are not told explicitly who makes the service vestments for officiating in the Tabernacle. Who does “they” refer to in these verses?

- Contrast the role of the unnamed artisans in these verses with that of Moses. Why do you think Moses is given prominence in these verses?

- Read the Another View section by Lisbeth S. Fried, on page 560.

- Our parashah contains descriptions of the priestly vestments, as well as the hangings and curtains to be used in the Tabernacle for both function and decoration. What does Fried say about the role of women in producing textiles in the ancient Near East?

- Although women are mentioned in other sections of Exodus relating to the giving of gifts to construct the Tabernacle (Exodus 35:22 and 36:6) and as artisans who constructed the Tabernacle (35:26), they are not mentioned in this parashah. How does Fried suggest we can reconstruct women’s role in producing these textiles?

- Read Proverbs 31:19 and II Kings 23:7. How do these verses help your understanding of the contributions of female artisans to the Tabernacle?

- Read Post-biblical Interpretations by Lisa J. Grushcow, on pages 560–61.

- What, according to Grushcow, is the most common explanation in rabbinic tradition for the association of women with Rosh Chodesh?

- How do other sources, which have their roots in Exodus 40:17, also link women with Rosh Chodesh? How do these sources view the role of women’s support in the construction of the Tabernacle?

- What, according to Midrash Sh’mot Rabbah 48.4, is the connection between Bezalel, one of the two chief artisans of the Tabernacle, and Miriam? How, through Bezalel, does Miriam contribute to the Tabernacle? How do women, according to Grushcow, play key roles at the beginning and end of Exodus?

- How do you react to Grushcow’s idea that women have a special ability to discern when a cause is worthy of their generosity?

- Read “Bezalel” by Amy Blank, in Voices on page 564.

- Read Exodus 38:22, the inspiration for this poem.

- What does the poem’s first line tell us about the point of view of the speaker (Bezalel) in the poem? What impact did that introductory line have on you as a reader?

- What, according to the poet, was Moses’ understanding of Bezalel’s role in constructing the Tabernacle? How was Moses’ view limited, according to Bezalel?

- According to Blank, what are the differences between Moses’ approach to constructing the Tabernacle through “words of command” and Bezalel’s perspective as an artist?

- According to the poem, what kinds of leadership skills does Moses use to help Bezalel be a leader of the artisans under his command? What do you think of this model of leadership?

- Describe a situation when you were involved in a significant project or task that involved others. How could the models presented in this poem have assisted you in completing that project?

THEME 2: COMPLETING THE TABERNACLE “TO DO” LIST

Parashat P’kudei concludes with a dramatic scene: the entrance of God’s presence into the Tabernacle. The text prepares the reader for this climactic event by subtly comparing the construction of the Mishkan to God’s creation of the universe and thus placing Moses—in his role as general contractor of the Tabernacle—in an analogous position to the Creator of the world. Before God’s presence can enter the Tabernacle, there are final steps that must be accomplished: The people must bring the Tabernacle, with the Tent of Meeting and all that it contains, to Moses. Moses then blesses the people. God then gives specific instructions, a final “to-do” list, about when and how the Tabernacle should be set up. The text’s emphasis on these specific steps reminds the reader of the divine origin of the Mishkan’s blueprint, the connection of the Mishkan to God’s redemption of the people from Egypt, and the link between the Mishkan and God’s covenant with the Israelites.

- Read Exodus 39:32–43.

- The word “completed” in verse 32 (vateichel) is from the same root as the verb used in Genesis 2:1–2 to describe God’s completion of the creation of the world (vay’chulu and vay’chal). Likewise, Exodus 39:43 contains echoes of the Creation story. Compare Exodus 39:43 with Genesis 1:31–2:3. What connections do you detect between these two texts? (Note that the verb translated as “surveyed” in Genesis 1:31 [vayar] is the same verb translated as “saw” in Exodus 39:43 [vayar].) What do these allusions to the Creation story suggest about the Tabernacle and its significance? (See the Central Commentary on Exodus 39:32 [“completed”] and 39:43.) In Exodus 39:43, Moses blesses the Israelites who contributed materials for and did the work of constructing the Tabernacle. Why, in your view, does Moses offer the blessing rather than God?

- Compare Exodus 39:32 with 39:42–43. What does the phrase communicate about Moses’ role in the completion of the Tabernacle? (See the Central Commentary on 28:22, 39:2, 39:32 [“as YHVH had commanded Moses”], and 40:17–33.) Why, in your view, does the parashah present Moses as the primary actor in the construction of the Tabernacle?

- Read Exodus 40:1–2.

- What is the significance of the fact that the Tabernacle is erected on “the first day of the first month”? What does the timing suggest about the role of the Tabernacle in the life of the people?

- According to the Central Commentary, the account of the completion of the Tabernacle that begins in these verses alludes to both the Creation story and the Exodus story (see Meyers’ introduction to 40:1–38 and her comment on verse 2 [“first day of the first month”]). How does the Tabernacle relate to the Exodus and Pesach? What are the implications of these connections?

- The causative form of the verb k-w-m (“you shall set up”) is used in verse 2 to describe the physical setting up of the Tabernacle. This form is also used in Exodus 6:4 in connection with the establishment of the covenant between God and Israel. How does the use of this verb in our parashah strengthen the connection between the covenant and the establishment of the Tabernacle? How does this connection make the Tabernacle more “God-worthy” for habitation?

- Read Exodus 40:34–38.

- Once Moses completes the work of setting up the Tabernacle, God’s presence appears as a cloud (v. 34). How does the association of the cloud with the divine presence in this verse compare with other times in which God’s presence appears to the people in this way (see Exodus 13:21, 33:9–10, 34:5)?

- Exodus 40:35 states that Moses is unable to enter the Tent of Meeting because God’s presence fills the space. Compare this verse with Exodus 33:7–11. How do these passages differ? How might you explain the seeming contradictions? How does Meyers account for the differences (see the Central Commentary on 33:7–11 and 40:35)?

- The root sh-k-n (“to dwell” or “to settle”) appears twice in Exodus 40:35, the first time as the cloud “settles” on the tent of Meeting and the second time in the Hebrew word for the Tabernacle (Mishkan). What does the repetition of this root suggest about the function of the Tabernacle? Read Exodus 25:8, which contains the same verb. What does this verse add to our understanding of the purpose of the Mishkan?

- Read the Contemporary Reflection by Noa Kushner, on pages 562–63.

- How, according to Kushner, did learning from their past mistakes enable the Israelites to make an earthly place where they could encounter God?

- Why is the physical representation of God in this parashah surprising?

- How do the physical manifestations of God in this parashah differ from the physical nature of the Golden Calf?

- How do the physical manifestations of God in this parashah—and elsewhere in the Torah—show the potential of familiar, natural things to be “bent and shaped in unnatural, divine ways” (p. 563)?

- In Exodus 40:38 God appears “in the view of all the house of Israel.” According to Kushner, what did the Israelites learn about worshipping idols and about the nature of their relationship to God from God’s physical expression?

- What can Exodus 40:34–38 teach us about looking for visual “evidence” of God’s presence in the world? Can you think of a time when you saw such visual evidence of the divine? In what types of places have you experienced God?

- Read “At the Tent of Meeting” by Sherry Blumberg, in Voices on page 566.

- What connection does the poet make between “the tent” and “the text”?

- Why do you think the poet describes herself as “Your humble daughter”?

- Where are you more likely to encounter a sense of God’s presence, in holy places or through the study of sacred texts?

- Read “Psalm 32: A Song of Endings and Beginnings” by Debbie Perlman, in Voices on page 566.

- Whereas Moses encounters God in the Mishkan, the poet discovers God “inside each completion.” Can you think of a time when you felt a spark of the divine in a moment of completion?

- How might marking our “starts and stops” by praising God’s name help us to “mold a new shape for our completions”?

- What does the poet suggest about the relationship between marking the completions of our lives and moving “to new beginnings”? What is God’s role in this process?

- How has marking a completion—either routine, joyous, or sad—helped you to move forward?

Overarching Questions

As you study these parts of the parashah, keep in mind the following overarching questions. if time permits, conclude the class with these broader questions:

- How do you understand the human need for a tangible sense of God’s presence?

- How, in your view, can we create sacred spaces in our own lives? What are the differences between creating such spaces individually and as part of a community?

- The Tabernacle and the service vestments for the priests are created using beautiful fabrics, precious metals, and jewels. How do beautiful physical surroundings contribute to sacred space? In what other ways can space be made sacred even if the surroundings are not so beautiful?

Closing Questions

- What new insight into the Torah did you gain from today’s study?

- What other new insights did you gain from this study?

What questions remain?