Parashat T’rumah Study Guide Themes

Theme 1: Divine Architecture: Designing an Earthly Meeting Place for God and Israel

Theme 2: It Takes a Community: Team-Building God’s Earthly Residence

INTRODUCTION

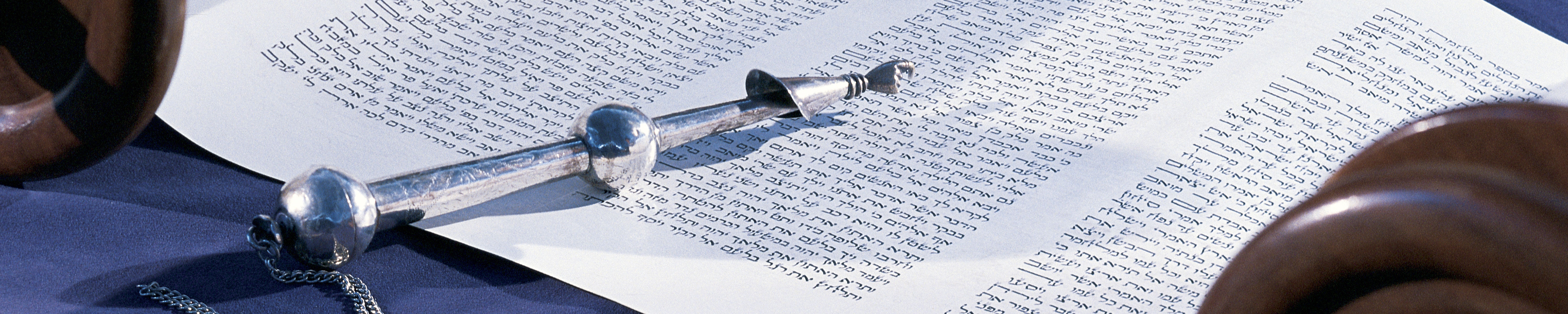

The divine presence is everywhere as the Israelites begin the forty-year journey in the wilderness from which they will emerge as a people: freeing the Israelites from Egyptian bondage, saving them from the mighty Egyptian army, revealing the rules by which they are to live as they stand—amidst thunder and lightning—trembling at the foot of Mount Sinai. The Israelites now have the laws by which they will live, and that will enable them to inhabit the land that God promised to their ancestors. the process of becoming a people capable of governing themselves and possessing the Promised Land involves enormous change and uncertainty, and the people yearn for God’s presence. The Israelites must find ways to keep God in their midst, to know that the God of signs and miracles is with them on earth. The Israelites—like their ancient Near Eastern neighbors—need an earthly dwelling place for God. Parashat T’rumah gives detailed instructions for constructing the divine earthly residence. God instructs the people to provide t’rumah—voluntary gifts—for the construction of the tabernacle. It is these heartfelt contributions of the Israelites, working together, that will enable God to dwell in their midst.

BEFORE GETTING STARTED

Before turning to the biblical text and the questions presented below, use the introductory material in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary to provide an overview of the parashah as a whole. Draw attention to a few key quotations from the introduction to the Central Commentary on pages 451–52 and/or survey the outline on page 452. This will help you highlight some of the main themes in this parashah and give participants a context for the sections they will study within the larger portion. Also, remember that when the study guide asks you to read the biblical text, take the time to examine the associated comments in the Central Commentary. This will help you answer questions and gain a deeper understanding of the biblical text.

THEME 1: DIVINE ARCHITECTURE: DESIGNING AN EARTHLY MEETING PLACE FOR GOD AND ISRAEL

How do human beings construct an earthly residence for God? The instructions for building the tabernacle contain a wealth of details about the kinds of materials to be used in the tabernacle and about how these materials should be fashioned into a finished structure. The tabernacle will be constructed of the finest, most valuable earthly elements and will contain symbols that evoke God’s sovereignty. It will be a place where the Israelites can experience God’s presence on earth. the tabernacle is to be both an earthly sanctuary for God and a symbol of God’s constant, dynamic presence among the people.

- Read Exodus 25:1–10.

- What is the purpose of the gifts that the people are asked to bring to God? Why do you think Moses is told to list the requested gifts before telling the people the purpose of these gifts?

- According to the Central Commentary on 25:8, what does the root of the word sanctuary (mikdash) mean? What does this root indicate about the function of this dwelling? What other Hebrew words do you know from the same root?

- According to the biblical text, what is the purpose of the tabernacle? What is significant about the fact that God wants to dwell among them (the people) instead of in it (the tabernacle)?

- Read the first three sentences of Carol Meyers’s introduction to the parashah (p. 451) and her comment on “among them” in 25:8 (p. 454). What do the people gain by having God dwell in their midst? How does the tabernacle help “negotiate the tension” between divine freedom and transcendence on the one hand and divine immanence on the other?

- According to Meyers’s comment on “dwell” in 25:8, how does the verb sh-k-n (the root of the word Mishkan/tabernacle) differ from the more common word for “dwell” (y-sh-b)? What does the difference tell us about the design of the Tabernacle?

- In 25:9, God instructs the people to make the Tabernacle according to “the pattern of the Tabernacle and the pattern of all its furnishings.” Meyers argues that the Tabernacle is modeled after God’s heavenly abode. Why do you think God gives such explicit plans for the tabernacle rather than leaving the design to the people?

- Read Leviticus 26:11, which is part of a list of blessings God will bestow upon Israel if the people follow God’s laws. the word translated as “abode” (mishkan) is the same term in our parashah for “Tabernacle.” How is the term used differently in Leviticus 26:11? What is the relationship between the assurance of God residing with the people and the promise not to spurn them? How does this passage inform your understanding of the purpose of the Tabernacle?

- Read Exodus 25:17–22, which describes the cover of the Tabernacle (the kaporet).

- In the Central Commentary on 25:17, Meyers writes about the origins of the Hebrew word kaporet. Read I Samuel 4:4 and Psalm 99:1–5 and compare these descriptions of the Ark to the one in these verses. What do we learn from this comparison?

- What are cherubim (see the Central Commentary on 25:18)? Why might these creatures have been part of the decorations for the tabernacle’s cover?

- Meyers states that the placement of the cherubim on either side of the Tabernacle’s cover “forms a throne, with the cover as a footstool for God’s unseen presence.” What is the concept of God suggested by these verses?

- In 25:22, God tells Moses that the Tabernacle is the place where God will “meet with” the people. How does this statement relate to the other name for the tabernacle: the tent of Meeting? According to Meyers’s comments on 25:22, when might people seek a meeting with God, and what form would this meeting take? How does the view of God presented in this verse compare with the image of God suggested by 25:17–21?

- What does Meyers say is the purpose of God meeting with Moses “concerning the Israelite people” (25:22)? What is your reaction to the idea that this meeting takes the form of an oracle?

- Post-biblical Interpretations, pages 468–69:

- Read Ruth Gais’s comments on 25:8–9 on page 468. Gais writes that two important words in this passage, v’shachanti (“that I may dwell”) and mishkan (“Tabernacle”), share linguistic roots with the feminine noun Shechinah. How did the Rabbis understand this word? How is the term Shechinah used in the Talmud? What is the role of the Shechinah according to Jewish mystic tradition? How does learning about the evolution of this word contribute to your understanding of the contemporary Jewish feminist use of the idea of the Shechinah?

- According to Gais’s comment on “so shall you make it” (25:9), some rabbinic commentators believed that God’s directions for building the Tabernacle were given after the incident of the Golden Calf, which occurs later, in Parashat Ki Tisa. What connection do the Rabbis see between the Golden Calf incident and the instructions for building the Tabernacle? How does Midrash Sh’mot Rabbah 35a describe the reasons for the construction of the Tabernacle? How does the role of Moses in this midrash change your understanding of the reason for the Tabernacle’s construction and God’s role in it? What does Nachmanides believe about the reason the tabernacle was constructed?

- Some collections of midrash portray the Tabernacle using marital imagery. How do these interpretations add to your understanding of the importance of the Tabernacle?

- In her comment on 25:18 (p. 469), Gais writes that, according to BT Chagigah 13b, each cherub represents a different divine attribute. What does each of these attributes contribute to our understanding of God?

- Gais writes that in Sh’mot Rabbah 34:1, the Rabbis explain how the presence of God contracted (tzimtzum) in order to meet with Moses. How does this image add to our understanding of God’s accessibility?

- Read “Creation,” by Nechama Gottschalk, in Voices (p. 472).

- Gottschalk writes of being “filled with wonder and awe” at God’s creation. She contrasts these feelings with the knowledge of the harsh realities of the world. How does Gottschalk manage the tension she feels between the closeness she feels to God and the pain, suffering, and destruction she sees in the world? Can you think of a time when you felt a similar tension?

- At the beginning and end of the poem, Gottschalk writes of how she experiences God’s presence. How do these experiences relate to the painful realities described in the middle of the poem?

- How does the poem connect to the instructions for the Tabernacle in this parashah?

- What is the view of God expressed by Gottschalk in this poem? How does this compare with your experience or view of God?

- Read “please with gentleness” by Haviva Pedaya in Voices (p. 472).

- How does the poet interpret the word b’tocham, “that I may dwell among them” (Exodus 25:8)? How does Pedaya’s interpretation of this word alter your understanding of its possible meaning?

- According to the poet, what is the relationship between “your dwelling in me” and “your giving me a spirit”?

- How does the poet understand the relationship between her experience of God’s “spirit” and prayer?

- The poet writes that when she prays, she “lacked nothing” and later that “I desire nothing.” Have you ever experienced similar feelings during prayer or at another moment?

- Read “The Compassion of the Shekhinah,” by Ellen Frankel, in Voices (p. 472).

- What attributes, according to Frankel, does the Shechinah possess?

- How is Frankel’s interpretation related to the rabbinic views of the Shechinah (see 3a above)?

- In Frankel’s view, the Shechinah acts both as a restraint on God’s “upraised hand” when it is raised to punish “Her children” and as one who punishes those children Herself. In this way, Frankel reminds us of the Talmud’s interpretation of the cherubim (see 3d above). What is the impact of combining the aspects of divine mercy and divine justice in the figure of the Shechinah?

- What is your reaction to Frankel’s use of feminine pronouns (“Her” and “Herself”)? How does our use of gendered language for God have an impact on how we view God?

THEME 2: IT TAKES A COMMUNITY: TEAM-BUILDING GOD’S EARTHLY RESIDENCE

How does a group of people become a community? Parashat T’rumah teaches us that working together toward a common goal helps the Israelites build an identity as a people. Although God gives explicit instructions for how the Tabernacle is to be built, the construction materials must come from voluntary donations, motivated by the heartfelt longing of the people to have God in their midst. It is only the combined efforts of the people that will establish God’s earthly residence.

- Read Exodus 25:1–9.

- How would you categorize the various kinds of gifts God desires?

- According to Meyers’s comment on 25:2, what is the meaning of the word t’rumah, from which this parashah takes its name? What difference does it make that the materials for the Tabernacle are collected from donations instead of taxes? What is the difference psychologically between being required to give and being asked to give?

- Compare the wording of 25:2 (which is part of what Carol Meyers identifies in the introduction to the parashah as “the prescriptive Tabernacle texts”) to the wording of Exodus 35:22, 35:29, and 36:6 (part of “the descriptive Tabernacle texts”). How do these latter verses enlarge your understanding of who “every person” in 25:2 includes? We read that the gifts should come “from every person.”

- In 25:2, we read that every person whose heart is “so moved” (yid’venu) should bring a gift. (The Hebrew root n-d-b means to “urge on” or “prompt.”) Why do you think the phrase “whose heart is so moved” was added to the instructions?

- Read Meyers’s comment on the Hebrew word tavnit (“pattern”) in 25:9. How do you understand the need of the ancient Israelites to construct an earthly structure resembling God’s “heavenly abode”? How does the knowledge that the Tabernacle should mimic God’s heavenly “residence” help us to understand the elaborate instructions that follow?

- Exodus 25:10–40 contains instructions for the interior furnishings of the Tabernacle. Read Meyers’s introduction to this section on page 455.

- Read Exodus 25:10–16. What, according to Meyers, is the meaning of the word aron (“Ark”)? How do the instructions for building this aron and the materials to be used demonstrate its significance? Why is the edut (“pact” or “treaty”) in 25:16 so sacred to the Israelites (see exodus 31:18)?

- Exodus 25:17–22 describes the cover of the Ark. In her comment on 25:17, what does Meyers suggest are the possible meanings of the word kaporet (“cover”)? How does each of the possible meanings of this Hebrew word help you to understand the significance of the kaporet? What do the images of the cherubim add to your understanding of the importance of the Ark?

- Exodus 25:23–40 describes the furnishings of the Tabernacle’s outer, main room. Why, according to the Central Commentary on 25:30, is bread featured so prominently here? Who may have baked this bread? These verses contain a description of the golden menorah that is to be constructed for the tabernacle’s outer room. What does Meyers say in her comment on 25:31 about the significance of this lampstand in post-biblical Jewish tradition?

- Exodus 26:1–37 contains instructions for the structure of the Tabernacle.

- In 26:22, we read that the rear interior section of the Tabernacle is “to the west.” According to Meyers, what is the significance of the east-west direction of this space? What do you think is the importance of having the rising sun at the equinox shine on the Ark?

- The textile partitions described in 26:31–37 divide the interior space into two parts: one designated kodesh (“Holy”) and one kodesh kodashim (“Holy of Holies”). The latter space is to contain the Tabernacle’s most sacred object, the Ark. What do these designations tell us about the purpose of the tabernacle?

- Exodus 26:31 states that a parochet (“curtain”) shall be made for the Tabernacle. In her comment on “make a curtain,” what does Meyers note about the significance of this curtain in Jewish life? According to the first paragraph of the introduction to the parashah (p. 451), how does the tabernacle differ from the synagogue?

- Exodus 27:1–19 contains instructions for the courtyard of the Tabernacle.

- What, according to Meyers, is the purpose of the courtyard? Why were only certain people allowed to enter parts of the Tabernacle?

- Read the first paragraph in the Central Commentary on page 465, which discusses the enclosure of the Tabernacle (27:9–19). What are the purposes of the enclosure?

- Read “Another View” by Elizabeth Bloch-Smith on page 467.

- At the end of the introduction to Parashat T’rumah (p. 452), Carol Meyers points to several biblical texts that “challenge the popular impression that this holy edifice is the result of exclusively male efforts.” What types of evidence does Bloch-Smith introduce as she shows how women may have been involved in activities reflected in the description of the Tabernacle and its furnishings? What do we learn from various biblical texts about the role women played in producing textiles?

- What role might women have played in producing textiles?

- How does the archeological evidence expand our understanding of methods of weaving in the biblical period?

- According to Bloch-Smith, what sorts of textiles did women in ancient Israel produce, and why?

- How does the Another View section change the perception of the Tabernacle you had from simply reading the biblical text? Particularly if you sew, knit, or weave, how does the information Bloch-Smith presents influence your relationship to the parashah?

- Read the Contemporary Reflection by Denise L. Eger on pages 469–470.

- How does the Tabernacle (Mishkan) serve as what Eger calls the “symbolic core” of the Israelites?

- The Israelites must work together to construct the Mishkan. According to Eger, what purpose is served by having the people build the Mishkan?

- What is the difference between the work the Israelites were forced to do in Egypt and this construction?

- How, according to Eger, do the various parts of the Tabernacle remind us of contemporary synagogues? How do you think we differ from or are similar to our ancient ancestors in needing an earthly place where we can communicate with God?

- How does Eger believe we bring “the realm of the holy” into our lives by supporting Jewish communal institutions?

- Eger suggests that building the Mishkan helped transform our ancestors from slaves to free people, capable of constructing God’s “home on earth.” How does our work to support Jewish communal endeavors transform us?

- According to Eger, what does this parashah teach us about the importance of t’rumah—voluntary gifts that come from the heart—in the building of sacred community?

- Read “Before,” by Yocheved Bat-Miriam, in Voices on page 471.

- How, according to the poet, did women “in bygone days” approach the Divine?

- What is the poet’s attitude toward the contributions of women to “the holy arks”?

- Bat-Miriam, in the poem’s second to last stanza, makes reference to Hannah (read chapter 1 of I Samuel). How does the poet contrast Hannah’s way of approaching God with that of the women of “bygone days”?

- How does the poet contrast her own approach to God with that of Hannah?

- Bat-Miriam positions herself, and Hannah, in contrast to the women of “bygone days” in their approaches to God. does the poet make a judgment about which approach she prefers? If so, what do you think about her point of view?

- What are some of the ways in which you approach the Divine?

- Read “T’rumah,” by Laurie Patton, in Voices on page 471.

- What objects does Patton describe in the first three stanzas of the poem? What do these items have in common? How do they relate to the description of the Tabernacle and its furnishings in this parashah?

- How does the poet, in the final stanza, make the connection between the poem and the parashah explicit?

- What connection does the poet make between our efforts to “make tiny worlds and shed skins, and seek warm winds” and seeking connection with God?

- What is the relationship, according to the poet, between our efforts and God’s graciousness?

- In what other ways do “we cry to You”?

- Can you think of a time in your life when you felt that God heard your cry and responded with graciousness?

Overarching Questions

As you study these parts of the parashah, keep in mind the following overarching questions. if time permits, conclude the class with these broader questions:

- How do you understand the need of the Israelites to build a structure where they could experience God in their midst? Are there places you associate with God’s presence? What is it about these places that are conducive to feeling God’s presence?

- In Jewish tradition, God is seen as both transcendent (“everywhere”) and immanent (“right here”). How do you resolve this dynamic tension in your experience of God?

- How does working within a community to build something of value differ from working as an individual? How does working together as a community brings God’s presence into the world?

CLOSING QUESTIONS

- What new insight into the Torah did you gain from today’s study?

- What other new insights did you gain from this study?

- What questions remain?