Parashat Tzav Study Guide Themes

Theme 1: The Roles and Privileges of Women as Members of Priestly Families

Theme 2: Women’s Role in Crafting the Priestly Garments

Theme 3: Did Women Offer Sacrifices?

INTRODUCTION

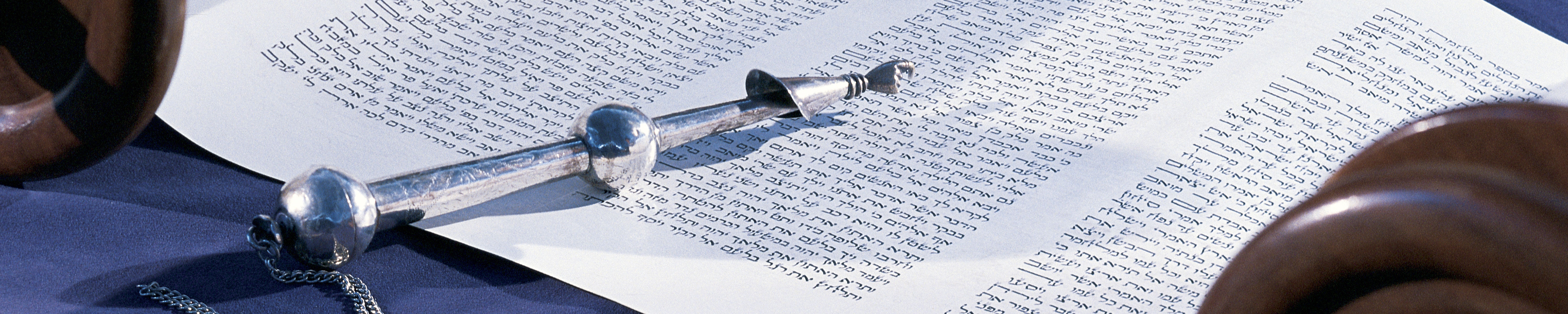

Tamara Cohn Eskenazi introduces the goal of the book of Leviticus as “aim[ing] to shape the Israelites into a holy people and to safeguard the purity that it con-siders essential for contact with the holy” (p. 567). The Hebrew name, Vayikra, comes from the first word of the book, in which God calls (k-r-a) to Moses in order to give him the instructions that constitute the majority of the book. Leviticus depicts the world as a fundamentally ordered universe. When boundaries are not appropriately respected and the natural harmony is upended, a person can, and should, restore the world to its natural order. According to Leviticus, proper use of the sacrificial system provides the means to achieve restoration.

Parashat Vayikra (Leviticus 1–5), the first parashah of the book, instructs the Israelites with regard to these sacrificial offerings. Parashat Tzav continues these instructions, but the focus shifts specifically to the priests, as opposed to the entire Israelite population. The first section of the parashah contains supplemental instructions to the priests regarding sacrifices, beyond what was given in the prior week’s portion. The second section concentrates on the ordination of the priests: God’s instructions for their ordination, Moses’ fulfillment of these instructions, and a final seven-day period of isolation for the priests.

This parashah does not mention women explicitly. Yet as Eskenazi points out, “it treats three areas that do involve women” (p. 593): the roles and privileges of women as members of priests’ families, women’s roles as they pertained to the formal priestly garments, and the question as to whether women offered sacrifices. These three areas provide the themes for the study guide of this parashah.

SUGGESTIONS FOR GETTING STARTED

Before turning to the biblical text and the questions presented below, use the introductory material in the The Torah: A Women’s Commentary to provide an overview of the parashah as a whole. Draw attention to a few key quotations from the introduction on pages 593–594, and survey the outline on page 594. This will allow you to highlight some of the key themes in this portion and help participants situate the section they are going to study within the larger parashah.

THEME 1: THE ROLES AND PRIVILEGES OF WOMEN AS MEMBERS OF PRIESTS’ FAMILIES

Maintaining the laws of the sacrificial system was part of the Israelite effort to ensure that the people lived according to God’s will. One part of this system involved preserving natural separations between disparate objects. However, the Torah recognizes that in daily life these boundaries would regularly be crossed and mistakes would happen. To rectify these mistakes, the people brought sacrifices, which were officiated over by the priests. the sacrificial system not only provided theological comfort for the people, but it also allowed for the continuation of the economic system that supported the Temple. The priests of ancient Israel did not own their own land; instead, they were sustained through portions of the sacrificial offerings designated for them and their families. In this parashah, we read of the ritual of the meal offering (Leviticus 6:7–16) and consider who was allowed to consume it.

- Read Leviticus 6:7–16.a.

- What piece of the meal offering is burned on the altar, and what is done with the rest of it? How do you understand the difference between the percentage given to God versus the percentage given to the priests?

- Leviticus 6:9–11 contains specific instructions regarding the portion of the offering that goes to the priests. What do you think is the significance of these details in the permission to use the meal offering?

- Read Tamara Eskenazi’s comment on Leviticus 6:11, which specifies that “only the males” may consume the offering.

- Why would only males be allowed to consume this food?

- What are the two possible ways to reading this statement?

- Which reading do you find to be more convincing?

- Read “Another View” by Hilary Lipka (p. 608).

- What purpose does Hilary Lipka believe the statement “only the males” (Leviticus 6:11) serves? In her reading, who is being excluded?

- What distinguishes men and women of the priestly line and thus allows men to eat offerings that fall under the rubric of “most sacred”?

- What types of offerings could the entire priestly family consume?

- What relationships allowed a woman attached to a priestly family to consume offerings? Which type of relationships did not confer this right to a woman? What does this tell you about the type of relationship that tied a woman to the priestly family?

- Read “Eating the Bones” by Ellen Bass (p. 612), which refers to the well-being sacrifice offered in the Temple.

- Read Leviticus 7:15–18. What do the women in the poem have in common with those who consume the well-being offering in the parashah?

- Does the description of the women in this poem remind you of anyone or any past experiences?

- Ellen Bass makes a connection between the consumption of food and love. Do you agree or disagree with her connection? Explain your answer.

THEME 2: WOMEN’S ROLE IN CRAFTING THE PRIESTLY GARMENTS

Women are not mentioned in parashat Tzav. This absence, however, does not mean they did not play a behind-the-scenes role in the events recorded in this parashah, which emphasizes the clothing that the priests wore while they performed their ritual duties. Tamara Eskenazi notes that “the fabrics that the ‘skilled women’ wove for the Tabernacle (Exodus 35:25) were nearly identical to the material specified for the priestly garments” (note to Leviticus 6:3 on p. 595). This observation leads to the suggestion that women may have been involved in creating the priestly garments. This section of the study guide will explore women’s explicit roles in creating fabrics in other parts of the Bible, which helps us appreciate their possible role in this parashah.

- Read Leviticus 6:1–3 and 8:1–9.

- How would you describe the clothes the priests wore? What role did the clothes themselves play in the priestly functioning?

- How does this compare to the role we assign to clothing in our own society?

- There are several other accounts that attest to the role women likely played in preparing the priestly clothing.

- I Samuel 1–2 tells of Hannah, the second wife of Elkanah, who could bear no children. Peninnah, Elkanah’s other wife, has children, but Hannah has none. When they go to the Temple to bring the yearly sacrifice, Elkanah gives portions to Peninnah and her sons, while Hannah receives only for herself (though she does receive a double portion). When she prays to God asking for a son, God hears her prayer, and Hannah gives birth to Samuel. As promised, after Samuel is weaned, she dedicates her son to serve God in the Temple for the rest of his life. Every year Hannah weaves a new robe for Samuel, as we read in I Samuel 2:18–19: “Samuel was engaged in the service of YHVH as an attendant, girded with a linen ephod. His mother would also make a little robe for him and bring it up to him every year, when she made the pilgrimage with her husband to offer the annual sacrifice.”

- How does Hannah remain a presence in Samuel’s life even once he has been dedicated to God?

- What does this passage suggest to us about the possible role women may have played behind the scenes in our parashah?

- Read Exodus 35:25–26, which describes the role women had in making cloth for the Tabernacle.

- The translation says that the “skilled women” spun the cloth, but Carol Meyers notes that the literal translation is “every woman [with] wisdom of the heart” (p. 527). What is the difference between the two translations?

- How do you think the making of tapestries for the Tabernacle would compare to making priestly clothing?

- Does this example convince you that women played a role in creating the priestly garments? Why or why not?

- I Samuel 1–2 tells of Hannah, the second wife of Elkanah, who could bear no children. Peninnah, Elkanah’s other wife, has children, but Hannah has none. When they go to the Temple to bring the yearly sacrifice, Elkanah gives portions to Peninnah and her sons, while Hannah receives only for herself (though she does receive a double portion). When she prays to God asking for a son, God hears her prayer, and Hannah gives birth to Samuel. As promised, after Samuel is weaned, she dedicates her son to serve God in the Temple for the rest of his life. Every year Hannah weaves a new robe for Samuel, as we read in I Samuel 2:18–19: “Samuel was engaged in the service of YHVH as an attendant, girded with a linen ephod. His mother would also make a little robe for him and bring it up to him every year, when she made the pilgrimage with her husband to offer the annual sacrifice.”

- Read the passage from “Clothes My Mother Made” by Hanna Zacks (p. 614).

- What does love do to transform the work of creating clothing for another person?

- Have you ever given or received something made especially for you? What was most significant about that gift?

- How does this poem help you understand the relationship between Hannah and Samuel?

- Read the selection from “The Tapestry of Jewish Time” by Nina Beth Cardin (p. 614).

- Nina Beth Cardin envisions the Jewish tradition as a shawl woven together. Explain her use of this metaphor. In what ways are we “a union of weavers”?

- What does she believe constitutes the fibers of the Jewish shawl? Would you add anything else to that list?

- Nina Beth Cardin describes two kinds of shawls, “open and loose” and “fine and tight.” Which Jewish traditions do you participate in that fit these descriptions? Explain your selections.

THEME 3: DID WOMEN OFFER SACRIFICES?

While women in ancient Israel were not allowed to be priests, a close reading of the biblical text suggests that they did participate in the sacrificial system by bringing prescribed offerings. This section of the study guide will examine the relevant evidence in order to answer the question, did women offer sacrifices? In addition, we will consider the way the Rabbis re-created the sacrificial system after the destruction of the Temple and the impact this had on women’s religious lives.

- Read Leviticus 7:11–15, which describes the well-being offering.

- When is the well-being sacrifice offered?

- What types of well-being offerings did people bring?

- Who does the biblical text indicate could offer a well-being sacrifice?

- Read the post-biblical commentary on Leviticus 7:12 (p. 609). What is the importance of the thanksgiving offering, according to the Rabbis?

- Read Numbers 30:4; i Samuel 1:3–4, 1:21, 1:24–28; and Proverbs 7:14.

- What do these passages indicate about women’s participation in the sacrificial system?

- Do you think we can transfer what we learn about women in these other biblical passages to the well-being sacrifice described in Leviticus 7:11–15? Why or why not?

- Read the Contemporary Reflection by Nancy Fuchs Kreimer, from “After the destruction of Jerusalem’s Temple . . .” (p. 610) through “. . . in Memory’s Kitchen in 1966 by Cara de Silva” (p. 611).

- How did the destruction of the Temple create a situation in which women became the ritual specialists of the Jewish people?

- How was that situation echoed by Jewish women during the Holocaust?

- Are there family recipes or traditions in your house that help you transcend difficult situations the way the recipes helped the women in the Holocaust? explain your answer.

- Read the selection from “To My Country” by Rahel (p. 612)

- What are the modest gifts that individuals offer to their country? How does this modesty compare to the biblical system of offering sacrifices?

- What are the sacrifices you believe Jews owe to the Jewish community? to their country? to Israel?

CLOSING QUESTIONS

- What new insight into the Torah did you gain from today’s study?

- What other new insights did you gain from this study?

- What questions are you left with?