Parashat Shemot Study Guide Themes

Theme: Saviors: Women as Rescuers and Redeemers

Part 1: The Midwives

Part 2: Lifesavers at the River

Part 3: The Midnight Heroine

INTRODUCTION

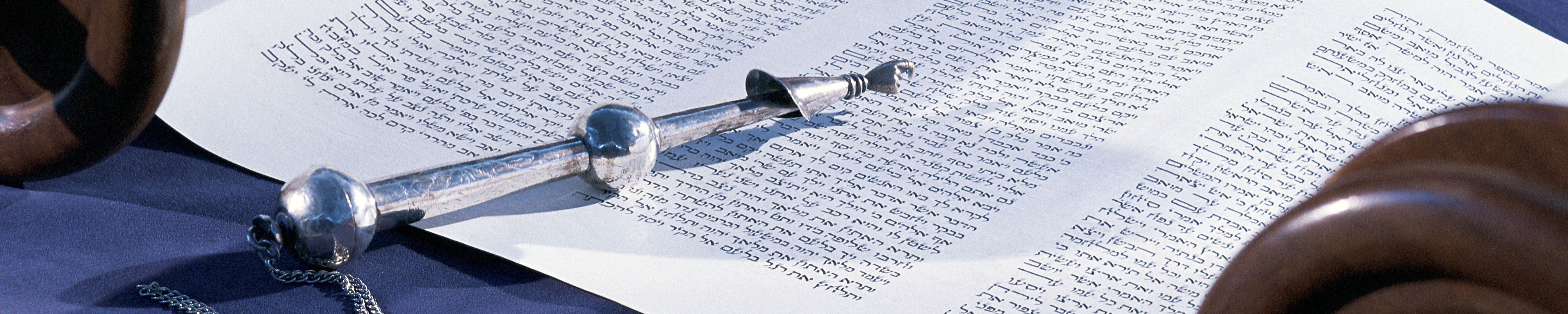

In Parashat Sh’mot, the Torah begins a new and significant chapter in the Israelite national history. The previous book, Genesis, focuses more narrowly on the founders of a people (the matriarchs and patriarchs) and on their complex relationships with one another and with their God. In exodus, called Sh’mot (“Names”) in Hebrew, the focus broadens and becomes communal and national. The spotlight now falls on the stirrings of nationhood. Complicated interpersonal relationships still abound, but the overall theme is one in which individuals are participants in a historical development larger than themselves. At the beginning of the first Torah portion in Sh’mot (referred to by the same title), we learn that the descendants of Joseph have died, and the Israelite experience in Egypt goes from one of security and prosperity to oppression and hardship. The national leader-to-be, Moses, is born, survives an early threat to his life, and begins the process that will ultimately lead to the liberation of his people from Egyptian servitude. This portion is particularly rich in its depiction of female characters. Six of them—two midwives, an Egyptian princess, and the mother, sister, and wife of Moses—function as nothing less than saviors of Moses and hence the people Israel. They work both independently and together, in the latter case pooling their intellectual, spiritual, and physical resources to accomplish their goals. In some of the stories, the women practice what we would call today “civil disobedience.” That is, at consider-able personal risk, these women directly defy edicts of the powerful. They also act as saviors in the broader sense, doing whatever is necessary to save and maintain life. This study guide will highlight the intelligence, resourcefulness, courage, and action of these women: Puah and Shiphrah, the midwives; Jochebed, Miriam, and Pharaoh’s daughter, the lifesavers at the river; and Zipporah, the midnight heroine.

BEFORE GETTING STARTED

Before turning to the biblical text and the questions presented below, use the introductory material in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary to provide an overview of the parashah as a whole. Draw attention to a few key quotations from the introduction to the Central Commentary on pages 305–6 and/or survey the outline on page 306. This will allow you to highlight some of the main themes in this portion and give participants a context for the sections they will study within the larger parashah. Also, remember that when the study guide asks you to read biblical text, take the time to examine the associated comments in the Central Commentary. This will help you to answer questions and gain a deeper understanding of the biblical text.

SAVIORS: WOMEN AS RESCUERS AND REDEEMERS

PART 1: THE MIDWIVES

Questions for Discussion

- Read Exodus 1:1–22, in which the power of Pharaoh is pitted against that of two midwives.

- What is the problem to which Pharaoh is responding? What is his stated concern about the fertility of the Israelites?

- According to Berlin’s comment on 1:7, how does the text’s use of key Hebrew verbs create a powerful image of the Israelite population increase?

- What is Pharaoh’s initial plan to address the perceived threat? What is the outcome of this plan?

- What is Pharaoh’s next plan? Why do you think he moves on to this second solution in verses 15–16?

- Note the ambiguity about the identities of Shiphrah and Puah. What are the two ways to interpret the phrase “Hebrew midwives”? According to Berlin’s comment on 1:15, what is their ethnicity? How does the way we interpret their ethnicity affect the way we understand their actions?

- What did the midwives do in response to Pharaoh’s edict? What did they say to Pharaoh when challenged? What was the outcome?

- What role does God play in this story?

- The names of the midwives are preserved in the text while that of the pharaoh is not. What messages can we draw from this fact?

- Read Susan Niditch’s Another View on page 324, which provides further insight into Pharaoh’s character and the significance of the midwives’ actions.

- What does Niditch’s commentary add to your understanding of the character and personality of Pharaoh?

- How does Niditch interpret the interaction between Pharaoh and the midwives? What does this commentary add to your understanding of the midwives and their actions?

- Read the Post-biblical interpretation on exodus 1:5, “Shiphrah and . . . Puah” (p. 324).

- Tal Ilan points out that the Rabbis recast Shiphrah and Puah as Jochebed and Miriam. Why do you think they may have made this choice? How do these new identities alter the story?

- Ilan argues that recasting Shiphrah and Puah in this way represents a limitation on women’s roles in the salvation of Moses and, by extension, of the Israelite people as a whole. What insight does this recasting give us into the mindset and concerns of the Rabbis?

- Would you agree or disagree with Ilan’s interpretation? Why or why not?

- Read the poem “Deliverance: Pu’ah Explains” by Bonnie Lyons, on page 328.

- In this poem, how does Puah explain why she and Shiphrah took the actions they did?

- According to Puah, with whom do the two midwives identify?

- What is Puah’s analysis of Pharaoh’s personality? How does the portrayal of Pharaoh in this poem compare to that found in the Another View?

- According to Puah in this poem, how did she and Shiphrah use their understanding of Pharaoh to achieve their own ends?

- Personal perspectives on Shiphrah and Puah:

- What other women in history acted like Shiphrah and Puah? Name historical women whose actions are analogous to those of the midwives. How are they viewed by the world at large, as saviors, as troublemakers, or as both?

- Can you think of a time when you or someone you know acted like Shiphrah or Puah?

- What motivated these heroic actions? What were the risks, and what were the rewards?

PART 2: LIFESAVERS AT THE RIVER

- Read Exodus 2:1–10, in which Moses’s sister (Miriam), mother (Jochebed), and Pharaoh’s daughter work together to save the infant Moses.

- What specific actions does Jochebed take to save her son? In what ways does she “contribute to liberation by judiciously engaging in acts of civil disobedience” (Niditch, Another View, p. 324)?

- In Parashat Noach, God instructs Noah, saying, “the end of all flesh has come [to mind] before Me, because the earth is full of violence on their account; look, now—I am going to wipe them off the earth. Make yourself an ark [teivah] of gopher wood; make the ark with rooms, and cover it with tar inside and out” (Genesis 6:13–14). This vessel protects Noah, his family, and two of every living creature until the Flood ends and the world is re-created. The Hebrew word for the basket into which Jochebed places Moses is the same as the word for “ark”—teivah. What does this word choice telegraph to the reader/listener about the significance of the events about to unfold? What does the word choice indicate about Moses’s role in the larger course of Israelite history?

- Read Berlin’s explanation of the role of wet nurses in the ancient Near east (see v. 9, “nurse it for me, and i will pay your wages,” on p. 312). How does the young Miriam utilize her understanding of this practice in her role as a rescuer? What personality traits does Miriam demonstrate in this scene?

- When Moses ultimately is returned by his mother to Pharaoh’s daughter, what does Pharaoh’s daughter do to “make” Moses her son? How does this action bind Moses to her? What personal traits does she demonstrate in this story? What might have motivated her to retrieve the basket and adopt the baby boy?

- Read the Post-biblical interpretation on Exodus 2:4, “And his sister stationed herself” (pp. 324–25), in which Tal Ilan describes how the Rabbis exegetically transformed the lifesavers, Miriam and Pharaoh’s daughter, into prophets.

- Why do you think the Rabbis wished to see these two women as prophets? How do the Rabbis add onto the biblical narrative in order to bolster their claim that these women are prophets?

- What characteristics did the Rabbis assign to these female characters? How do they compare with the description of Miriam and Pharaoh’s daughter in the biblical text?

- What potential problem do the Rabbis have with Pharaoh’s daughter being a prophet, and how do they resolve the problem? How does their resolution impact on your understanding of her character or the motivations for her actions?

- Read “Miriam” by Marsha Pravder Mirkin, “Epitaph” by Eleanor Wilner, and “On Adoption” by Lisa Hostein on page 329.

- In “Miriam,” according to Mirkin, what does Miriam say were the motivating forces behind her actions? What does Miriam tell the reader about herself? What does she tell the reader about how she is both different than and similar to Pharaoh’s daughter? What is your reaction to this interpretation?

- In “Epitaph,” what does Wilner suggest motivated Pharaoh’s daughter? According to Wilner, what was her ultimate fate? How does Wilner’s interpretation regarding the end of Pharaoh’s daughter impact your feelings about her and the exodus story as a whole?

- In “On Adoption,” Lisa Hostein speaks as an adoptive mother of a son. What are your experiences with the joys and challenges of adoption, your own or those of family or friends? How does your understanding of adoption affect your view of Moses’s two mothers, Pharaoh’s daughter and Jochebed?

- Read “Miriam Argues for Her Place as Prophetess” by Chava Romm, on page 330.

- Romm concludes her poem with Miriam saying, “Let us go,” that is, speaking in the first person plural. Why do you think Romm has Miriam speaking from this perspective? How does this perspective impact on your experience of the poem?

- What does Romm imagine Miriam is demanding? According to Romm, what is Miriam arguing against? What is she arguing for?

PART 3: THE MIDNIGHT HEROINE

- Read Exodus 4:19–26, in which Moses’s family has a terrifying experience at a night encampment.

- What is the mission on which Moses sets out at the beginning of this section?

- What was the threat that came upon Moses’s family at the “night encampment”?

- In her commentary on 4:24, Berlin notes that “it is unclear who the intended victim is: Moses—or his and Zipporah’s son, Gershom.” Given the ambiguity of the text, in your view, why would God want to slay Moses? Why would God want to slay Gershom? How does this incident affect your view of God as portrayed in this story?

- When the threat is revealed, what does Moses’s wife, Zipporah, do? What is significant about her actions? What personality traits do Zipporah’s actions reveal?

- According to Berlin, what might be an explanation for the seemingly odd placement of the story in 4:24–26 (see her introduction to this unit on p. 319)? What other explanations can you think of for the inclusion of this narrative in the early stages of the exodus story?

- Read Another View on page 324.

- In the last paragraph, Susan Niditch describes Jochebed, Pharaoh’s daughter, Miriam, Shiphrah, and Puah as “filled with a power rooted in moral reason, an ethical concern for life, and the capacity to empathize . . . judiciously engaging in acts of civil disobedience” as they defied a “male tyrant.” Would you consider Zipporah to also have defied a “male tyrant”? Why or why not?

- If so, who do you think was the “tyrant” of Zipporah’s story?

- Why do you think Zipporah took the action she did? What was the risk? What was the benefit?

- Read the Post-biblical interpretation on Exodus 4:25, “Zipporah . . . cut off her son’s foreskin” (pp. 325–26).

- According to Ilan, what are the two ways the Rabbis explain Zipporah’s actions in the biblical story, given the Talmudic disqualification of women as circumcisers?

- What is your reaction to the ways Rabbis recast the biblical story to minimize Zipporah’s role? What insight does this give you into Rabbinic problem solving?

- Through history, women have often been cast as “the power behind the throne,” thus denying their agency and influence, their visibility, and the status they deserve. What examples of this can you think of in our world today? Have you ever minimized or hidden your capabilities, your strength, or your “heroic” traits? What caused you to do so? How did you feel about your decision, at the time and now in retrospect?

- In Voices, read Shirley Kaufman’s “the Wife of Moses” on page 330.

- What perspective does this poem provide on the marriage dynamics between Moses and his wife?

- What are Zipporah’s resentments? What are her fears?

- What insights does this poem provide into Zipporah as a person? How does the portrayal of Zipporah in this poem compare with your own impression of her?

Overarching Questions

As you study these parts of the parashah, keep in mind the following overarching questions. If time permits, conclude the class with these broader questions:

- What do you consider to be the characteristics of a rescuer or redeemer?

- What do you think are some of the factors that motivate such individuals?

- Do you think that there are differences in how men and women fulfill these roles? If so, how would you characterize those differences? to what do you attribute these differences?

- Has there been a time in your life when you were in some way a rescuer or redeemer?

CLOSING QUESTIONS

1. What new insight into the Torah did you gain from today’s study?

2. What other new insights did you gain from this study?

3. What questions remain?

Explore Jewish Life and Get Inspired

Subscribe for Emails