Parashat Tazria Study Guide Themes

Theme 1: Birth, Impurity, Boys, Girls

Theme 2: The “Magic” of Renewal

INTRODUCTION

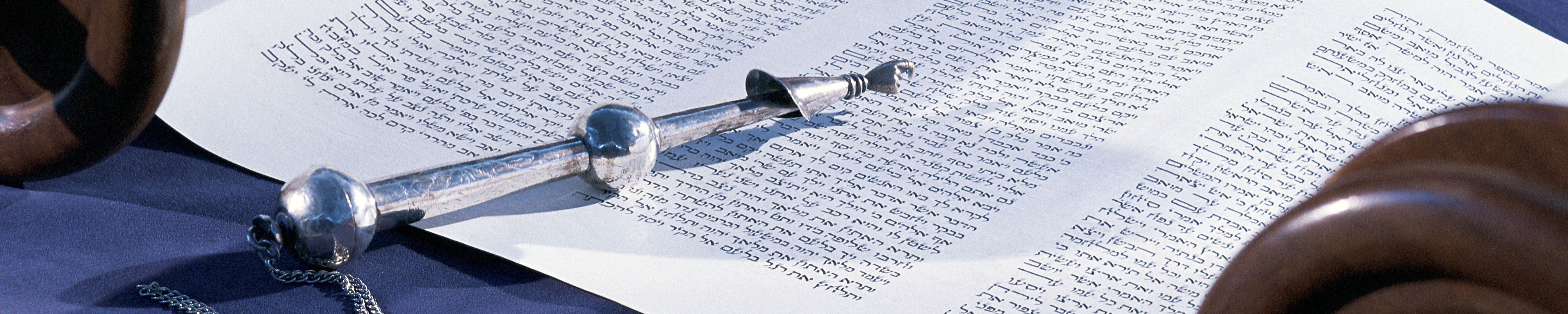

What does it mean to be “pure” or fit to perform ritual acts? How and why do individuals enter states of “impurity” and what restores them to well-being and wholeness? These are the concerns of Parashat Tazria, which addresses impurity derived from two sources: childbirth and an eruptive condition known as tzaraat. Tazria begins by discussing the condition of a woman immediately after giving birth and delineates the resulting limitations on her participation in communal religious affairs. Significant gender issues color these limitations, and an intricate set of rites is necessary to restore the new mother to ritual integrity. The parashah then goes on to describe in rather excruciating detail a condition called tzaraat, which is capable of infecting both skin and fabrics. Once so afflicted, the contaminated surface is capable of enormous power: it is potent enough to pollute the sanctuary, the place where God’s presence dwells. As a result, the affected persons or materials must be dealt with through a series of rigorous inspections and, if necessary, strict quarantine; a return to normal status occurs only after elaborate and thorough ritual acts. Two life-giving fluids—the blood of birth and the water of restoration—represent death and renewal. The symbol of death must be kept at bay lest it destroy all that is good and holy in the community. Impurity results at the point of intersection between life and death, the juncture of that which restores and that which destroys. Perhaps more than some others, this parashah may evoke strong reactions in those who study it. Participants will have the opportunity to share their own responses to some of this portion’s more provocative themes after a close reading of the biblical text and accompanying commentaries.

BEFORE GETTING STARTED

Before turning to the biblical text and the questions presented below, use the introductory material in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary to provide an overview of the parashah as a whole. Draw attention to a few key quotations from the introduction to the Central Commentary on pages 637–38 and/or survey the outline on page 638. This will allow you to highlight some of the main themes in this particular portion and give participants a context for the sections they will study within the larger parashah. Also, remember that when the study guide asks you to read biblical text, take the time to examine the associated material in the Central Commentary. This will help you to answer questions and gain a deeper understanding of the biblical text.

THEME 1: BIRTH, IMPURITY, BOYS, GIRLS

While childbirth renders a woman ritually impure, there are differences in the length of the time of impurity depending on the gender of her offspring. This theme focuses on the asymmetry of this phenomenon as well as the rituals required to reinstate a new mother to her normal status in the community. Participants are invited to speculate along with Jewish commentators through the centuries on possible explanations for these restrictions and rites.

Read Deuteronomy Leviticus 12:1–8.

- In Leviticus 12:2, what is the meaning of the Hebrew word tazria? Turn back to Genesis 1:11–12. How is the same root form used there? Contrast the meaning of the word in Leviticus with that in Genesis. How does the powerful use of the word in the Creation story inform or enhance your reading of Leviticus 12:2?

- As the comment on Leviticus 12:2 (“at childbirth”) explains, the translation in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary differs from other translations. How does the translation “When a woman at childbirth . . .” compare with Levine’s translation, “when a woman is inseminated”? How do these different translations influence your understanding of this verse?

- Leviticus 12:2 states that a woman after childbirth “shall be impure as at the time of her condition of menstrual separation.” What were the specific restrictions regarding contact with a new mother and a menstruating woman? Why do you think these two conditions were linked in this way?

- Leviticus 12:3 mentions the ritual of circumcision on the eighth day. What does elaine Goodfriend suggest about the possible power of circumcision and its effect on both mother and baby boy? How do her views compare with those of anthropologist Mary Douglas?

- What is the difference in the period of impurity for a woman who has given birth to a boy as compared to one who has delivered a girl? In both cases, there is a two-phased period of impurity. How does the initial time of impurity (seven days for a boy and fourteen days for a girl) differ from the second phase (thirty-three days for a boy and sixty-six days for a girl)?

- The commentary on this parashah lists a number of different explanations for the doubled period of impurity after the birth of a girl. According to the comment on Leviticus 12:5, how might this difference be explained? Which explanation or explanations do you find most convincing?

- For centuries, commentators have speculated about this imbalance in the periods of ritual impurity following the birth of a boy or girl. As a twenty-first-century commentator, how might you explain this imbalance? What would you like to add to this long-running conversation? What reactions does verse 5 evoke from you, and how do you integrate these reactions with your experiences with the relationship between gender and Jewish practices?

- According to Leviticus 12:6–8, what were the two types of sacrifices required of a woman who gave birth? How might the functions of these sacrifices—atoning for sin, offering thanksgiving, paying homage to God, cleansing the sanctuary of birth- generated impurity—be related to pregnancy, delivery, and new life?

- In her Another View (p. 650), Beth Alpert Nakhai presents an alternative reason for why the woman is impure twice as long after the birth of a girl. What is Nakhai’s theory? How does it compare with explanations presented in the Central Commentary? What does Nakhai suggest about the gender differences implicit in these purification rituals? How does her theory affect your ideas about the priestly authors of these rituals?

- In Post-biblical Interpretations (p. 651), Charlotte Elisheva Fonrobert discusses Mishnah Niddah 3:7, an early rabbinic discussion of embryology. What was the minority position of Rabbi Ishmael, and how did he use Leviticus 12:5 as his proof text? What was the majority position? What is the relationship between this verse and the debate in Babylonian Talmud B’rachot 60a about “vain prayer”? As a result, did you learn anything from the experience that you did not anticipate? If so, explain.

- What was the “somewhat farfetched” explanation of the double-length impurity following the birth of a girl offered by some talmudic rabbis in response to Rabbi Simeon (pp. 651–52)? How might this rationale have made sense to fifth-century readers? In today’s world, where do we see evidence of similar gender preference, and what are some of the consequences?

- If you have been pregnant and you anticipated or imagined having a child of one gender but then gave birth to the other, what was this experience like for you? As a result, did you learn anything from the experience that you did not anticipate? If so, explain.

- If you have been pregnant, what did you pray or hope for during your pregnancy? Were there some prayers/hopes that you shared with others and some that you kept to yourself? If so, what accounted for the difference?

- Read “Believe Me” by Esther Ettinger (p. 655). Why do you think the author chose this title? Whose voice is speaking here? The fragment in the poem, “weeping as he goes, weeping . . .” is from Psalm 126, the full section of which reads, “they who sow in tears / shall reap in joy. / He who goes weeping on his way, / bearing a bag of seed, / shall come back with a joyful shout, / carrying his sheaves.” How does this view of childbirth, reflected in the author’s use of the psalm, compare with childbirth as seen through the eyes of the biblical writers?

- Imagine that you have been given the task of designing a ritual for women making the transition in status from pregnancy to new motherhood. What elements would you include in such a ritual? Who would be involved? What would you name your new rite?

THEME 2: THE “MAGIC” OF RENEWAL

After the discussion of the laws for the impurity of a woman after giving birth (Leviticus 12), the focus of the parashah switches to laws for diagnosing and containing skin diseases (Leviticus 13). Following the suspicion of some sort of contagion (tzaraat), the priest enters, in a position that is both crucial and highly ambiguous. initially responsible for making a definitive “diagnosis” of tzaraat, the priest then goes on to fill an intriguing array of additional roles. Responsible for both afflicted individuals and the well-being of the community and the sanctuary, its most sacred structure, the priest utilizes a combination of rites and rituals to fulfill his obligations. Water plays a key role in this highly structured protocol, essentially functioning as an agent of life and renewal, the final step in a process that renews and restores. The questions below will focus on understanding the role of the priests and the power of water, which together had the ability to effect a transformative leap from exclusion to inclusion, returning formerly outcast individuals to their prior social status.

Read Leviticus 13:1–8, 13:45–58.

- According to the introductory comment on Leviticus 13:1–59 (pp. 642–43) and the comment on v. 3 (“leprous”), what is the meaning of the Hebrew word tzaraat? According to contemporary scholars, what skin conditions does it include? How has this word been incorrectly translated? Why does the JPS translation here use the word “leprous”? How do the different translations impact on your understanding of these verses?

- According to the text and the Central Commentary, how or why does one contract tzaraat?

- What is the role of the priests with persons who exhibit tzaraat? Are the priests carrying out a medical or public health function? What exactly can the priests offer those who are afflicted?

- Note that the priest continues to have personal contact with the afflicted person even after he or she has been isolated from the community. How does this impact your understanding of the purpose of quarantine? Given the priest’s ongoing association with the affected individual, what might be the various types of “contagion” from which the community needs protection?

- What do you consider to be the characteristics of one who helps to renew and restore others, bringing them from a state of brokenness to a place of greater wholeness?

- Has there been a time in your life when you functioned as such a person? When someone did this for you? If so, what were the elements of this process?

- A case of tzaraat also appears in Numbers 12, where Miriam and Aaron criticize their brother Moses’ choice of a wife. Read Numbers 12:1–13. How does this story help you understand the horror of tzaraat? On pages 642–43, Goodfriend explains that because of its particular symptoms, tzaraat was associated with a “decomposing corpse,” and thus with death. How does this association explain the need to deny those so afflicted access to sacred space? Goodfriend also explains that in some biblical sources tzaraat is regarded as divine punishment, although this is not the case in Leviticus. How does this compare with your own feelings about the source of disease? In your opinion, under what circumstances are individuals responsible for the ill health that befalls them?

- Tzaraat can infect both people and materials. According to Leviticus 13:47–58, what is the procedure necessary to render a fabric affected by tzaraat pure? What is the final step in the process? Read Goodfriend’s comment on verse 56. How does the biblical writers’ implicit recognition of people’s real needs affect your opinion of the purification rituals prescribed here?

- Read Contemporary Reflection on pages 652–53, in which Pauline Bebe discusses mikveh. Go back and read Leviticus 11:36 and 12:1–8 and then ahead to Leviticus 15:16 to understand how the Rabbis used these verses to develop the laws involving immersion in a mikveh. Why do you think that in biblical times water was designated as the primary agent of purification? Note that in 11:36, “a spring or cistern in which water is collected shall be pure” and that water is the final ingredient in the purification process of both people and fabrics.

- Read Genesis 1:1–10, in which water figures prominently and is first separated and then contained in the beginning of Creation. According to Bebe, how might regular use of a mikveh reflect this process of separation, waiting, anticipation, and reunion?

- Citing several rabbinic sources, Bebe links regular mikveh use with the impact that habitual rites may have on the lives of human beings. Can you think of a ritual that you perform regularly as well as a ritual that you perform only sporadically? In what ways does each act affect your life, and what is the impact of frequency with both?

- According to Bebe, how is water linked to spirituality? Think of times when you have been surrounded by water—bathing, swimming, in a hot tub or spa. What feelings or associations does water evoke for you? How did the experience affect your feelings about your body? Your spirit?

- What are the ways in which Bebe links the idea of water with the idea of mother? Think of the associations that you have to feeling comforted and renewed. What are they? What rituals, if any, support these experiences for you?

- Speaking to many contemporary Jewish women who may have never immersed in a mikveh, Bebe suggests that the mikveh has the potential to create spiritual “magic.” What are your experiences or associations to mikveh? Who or what formed your ideas about mikveh? How might you expand these ideas to consider using a mikveh in your own life?

Overarching Question

As you study these parts of the parashah, keep in mind the following overarching question. if time permits, conclude the class with these broader question:

- What do you think that human beings need to feel “good enough,” that is, worthy? What do you need?

Closing Questions

- What new insight into the Torah did you gain from today’s study?

- What other new insights did you gain from this study?

- What questions remain?

Explore Jewish Life and Get Inspired

Subscribe for Emails