Parashat V’zot Hab’rachah Study Guide Themes

Theme 1: Moses’ Final Blessing

Theme 2: The Death of Moses

Introduction

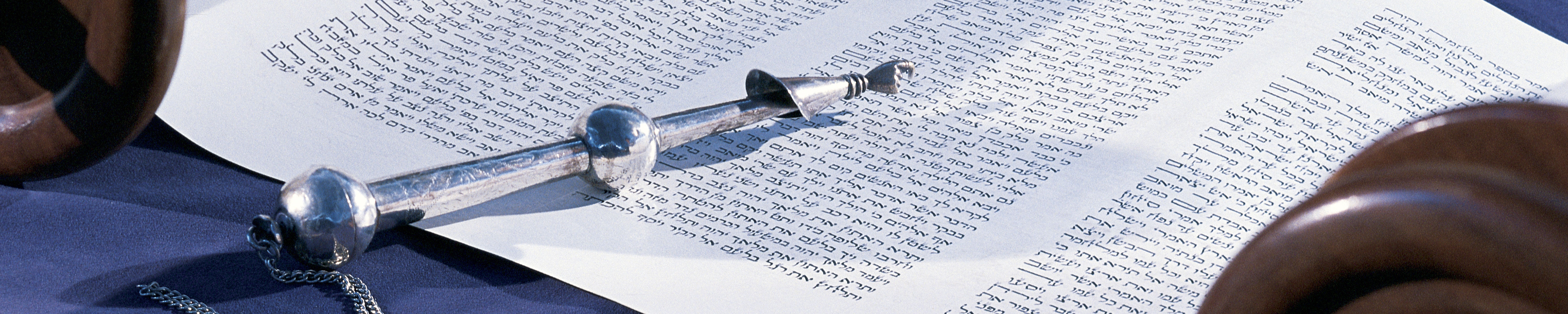

Parashat V’zot Hab’rachah (“this is the blessing”) begins with Moses’ final words to the Israelites and ends with a description of his death and burial. This parashah—the last in the Torah—is not part of the weekly Torah reading cycle. Rather, it is read on Simchat Torah, the holiday that celebrates the conclusion of the annual Torah reading cycle and the beginning of the new cycle. Moses’ last words to the people come in the form of a poetic blessing that looks to a time in which the Israelites will experience prosperity and security in the Promised Land. While Moses harshly criticizes the people in the prior parashah (Deuteronomy 32), here—as he is about to die— his words convey reassurance and praise, thus reminding the people that God will continue to protect, guide, and nurture them. While called a “blessing,” Moses’ words take the form of a father’s last words to his offspring (as in Genesis 27:28–29, 27:39–40, 49:1–27). Knowing that he will not enter the Promised Land with the people, Moses’ blessing conveys his final hopes and wishes for the future. The brief and poignant description of Moses’ death provides an opportunity to reflect on the life of Israel’s greatest prophet and his unparalleled contribution to the formation of the Israelite nation.

Theme 1: Moses’ Final Blessing

Moses delivers his last words to the entire people in the form of a poetic blessing. Like Jacob, who blessed his sons as he was near death (Genesis 49:1–27), Moses blesses the tribes of Israel. Unlike Jacob’s words, Moses’ message is positive and encouraging. Moses reminds the people that if they choose to live according to God’s Teaching and walk in God’s “steps,” they will have a prosperous and secure future in the Promised Land.

- Read Deuteronomy 33:1–5, which contains the prose introduction to Moses’ final blessing (v. 1) and poetic depictions of God (vv. 2–5).

- The Hebrew root b-r-k (bless) appears twice in verse 1. The second time the word appears, it is translated as “bade . . . farewell.” The literal translation of this verse is: “This is the blessing with which Moses, God’s envoy, blessed the Israelites before he died.” How does this literal translation add to your understanding of Moses’ words? In your view, what is the difference between giving someone a blessing and bidding someone farewell?

- The literal translation of the Hebrew phrase ish ha-Elohim (translated as “envoy” in v. 1) is “man of God.” Although this phrase appears elsewhere in the Bible—referring to Moses, other prophets, and King David—this verse is the only place we find this expression in the Torah. What does the literal translation of this phrase indicate about Moses’ relationship with God? What does the description of Moses as God’s “envoy” convey about his role as leader of the Israelites?

- What is unusual about the third-person reference to Moses in verse 4? According to the Central Commentary on this verse, how have commentators understood this reference? The first part of verse 4 is sung in some congregations after the Torah reading, while the Torah is wrapped and dressed. What makes this text appropriate for use in that liturgical context?

- Verse 2 depicts God as a warrior, verse 3 presents God as “Lover . . . of the people,” while verse 5 describes God as “King.” What do these different images convey about God? In your view, why do such varying metaphors for God appear in Moses’ final blessing?

- Read Deuteronomy 33:6–17, which contains Moses’ blessings for the tribes of Reuben, Judah, Levi, Benjamin, and Joseph.

- Why do you think Moses blesses the Israelite tribes rather than his own sons, Gershom and Eliezer?

- Verse 6 contains Moses’ blessing for the tribe of Reuben. The Central Commentary on verse 6 highlights this tribe’s vulnerability in choosing to live outside of the Land of Israel. What is the relationship, in your opinion, between the tribe’s decision to live outside the Promised Land and the brevity of their blessing?

- Compare the characterization of Judah in Moses’ blessing in verse 7 with that of Jacob’s blessing of Judah in Genesis 49:8–12. According to the Central Commentary on this verse, what may account for the difference?

- For what does Moses’ blessing of Levi (vv. 8–9) reward this tribe? To what incident does verse 9 refer? According to the Central Commentary on verse 9, what are the implications of the phrase “father and mother” when it appears in the Torah?

- The Hebrew word meged (“bounty”) appears five times in verses 13–16 as part of Moses’ blessing of Joseph. According to the Central Commentary on verse 13, what does this repetition highlight about the Promised Land? How does the biblical understanding of agricultural fertility differ from that of ancient Near Eastern polytheism, according to Tikva Frymer-Kensky?

- Read Deuteronomy 33:26–29, which contains Moses’ final words to the entire people.

- The Central Commentary on verse 26 notes that the phrase “there is none like God” is characteristic of Deuteronomy’s insistence on God’s “unrivaled divinity.” What is the significance of reemphasizing this view as part of Moses’ final words to the people?

- In what ways does the biblical text portray God in verses 26–29?

- Verse 27 describes God as having “arms everlasting.” According to the Central Commentary on verse 27, how does Isaiah 46:3–4 express a similar aspect of God? How does the context of each description differ? What aspects of God’s nature do these images project?

- What is the relationship, in your view, between the message of these final verses and the blessings Moses gives the tribes?

- Read Post-biblical Interpretations by Anna Urowitz-Freudenstein on pages 1284–85 (“May Reuben live and not die”).

- What do you notice about the differences between the seemingly similar language in the first and second parts of Moses’ blessing of Reuben?

- What meanings does Midrash Sifrei D’varim 347 find in these differences?

- Read the Contemporary Reflection by Naamah Kelman (pp. 1286–87).

- According to Kelman, the tone of Moses’ final blessing to the tribes of Israel differs markedly from his frequently stern tone in the rest of Deuteronomy. In your view, what might account for this difference?

- Kelman notes that Jewish tradition teaches that blessings are not to be passively received, but that we are required to act on them. Can you think of an example of a blessing that reflects this teaching? Is there a blessing you received that carried a demand for action with it?

- How can the possible connection between the Hebrew word for blessing (b’rachah) and the Hebrew word knee (berech) help us to expand our understanding of what we do when we recite a blessing?

- According to Kelman, how do Moses’ final blessing of the tribes and his approaching death relate to his humility (see Numbers 12:3)? How do you react to Kelman’s view that “affirming the future is what leadership is all about”?

- What does the idea that our dreams “may be realized by others who come after us” mean to you?

- Read the excerpt from “In the Jerusalem Hills” by Lea Goldberg, in Voices (p. 1289).

- What is the connection between “all the things / outside love” in the poem’s first lines and the narrator’s situation in life?

- What is the relationship between the repeated refrain “one more year, one more year / one generation more / one more eternity” and the narrator’s desire to live?

- How do these verses help you to understand what Moses might have been feeling during his blessing of the tribes?

- How do you relate to Goldberg’s description of the “lust for life” in those who are about to die as “vain”? In what ways have you seen this “terrible . . . longing” manifest in your own life or in the lives of those you love who are facing death?

Theme 2: The Death of Moses

The account of Moses’ death, while similar to that of other select characters in the Torah, contains unique elements that emphasize Moses’ incomparable status as Israel’s greatest leader. The text singles out Moses’ unusually intimate relationship with God and his accomplishments in leading the Israelites from slavery to the brink of nationhood. It also teaches that although good leaders must be appreciated and respected, human leadership is temporary. The biblical author reassures us that while there will never be another prophet like Moses, in the future there will be leaders like Joshua who continue in Moses’ able steps.

- Read Deuteronomy 34:1–4, which describes Moses’ survey of the Promised Land with God.

- In Numbers 27:12 and Deuteronomy 32:49, God commands Moses to ascend a mountain to view the Promised Land. In both of those verses, God reminds Moses that he will not be able to enter the land as a result of his actions in striking the rock and in breaking faith with God. Why do you think this reminder does not appear in Deuteronomy 34:1?

- From Moses’ vantage point atop Mount Nebo, it is not humanly possible to see “the whole land” (v. 1). Why do you think the biblical text describes what Moses sees in this way?

- How is the phrase translated as “see it with your own eyes” (v. 4) consistent with Deuteronomy’s emphasis on knowledge gained from firsthand experience (see Deuteronomy 4:3, 4:9, 4:34)? What is unusual about the firsthand knowledge Moses gains in this verse from seeing the land with his own eyes?

- Read Deuteronomy 34:5–7, which describes Moses’ death.

- Although the biblical text records many deaths at God’s command, this is the only time that we read that God buries someone (v. 6). What does this suggest about the relationship between God and Moses?

- The biblical text reports that Moses was “a hundred and twenty years old” when he died (v. 7). According to the Central Commentary on this verse, how can we understand this number?

- In your view, why does the text point out that at the time of his death, Moses’ “eyes were undimmed and his vigor unabated” (v. 7)?

- In verse 6 we read that no one knows where Moses is buried. What do you think are the implications of the fact that no one knows the site of Moses’ grave?

- The Torah records the deaths of a number of individuals, with varying details regarding their ages, the place and circumstances of death, and facts about the burial. The report of Moses’ death is the only one that contains every one of these elements. What accounts for this, in your view?

- Read Deuteronomy 34:8–9, which describes the mourning for Moses and the succession of Joshua.

- How does the biblical text describe Joshua (v. 9)?

- What is the significance of this description?

- Read Deuteronomy 34:10–12, the last verses in the Torah.

- In what ways do verses 10–12 serve as a eulogy for Moses?

- In your view, why does the text highlight the wondrous acts Moses performed on God’s behalf, resulting in the Israelites’ liberation from Egypt?

- What do these last verses in the Torah teach us about what was most important in Moses’ life?

- Read the Another View section by Tamara Cohn Eskenazi (p. 1284).

- Although “never again did there arise in Israel a prophet like Moses” (Deuteronomy 34:10), Eskenazi writes that there were other prophets who served as spokespersons for God. In Eskenazi’s view, why is Huldah Israel’s most successful prophet?

- How did Huldah’s actions contribute to the binding authority that Deuteronomy holds and to the preservation and transmission of its teachings to us?

- Read Post-biblical Interpretations by Anna Urowitz-Freudenstein on p. 1285 (“So Moses the servant of YHVH died there” and “[God] buried him in the valley in the land of Moab”).

- What is the connection between this parashah and Simchat Torah, when it is read?

- How does the medieval piyut (liturgical poem) “Azlat Yocheved” describe Yocheved’s search for her son, Moses?

- How does BT Sotah 14a use God’s burial of Moses (Deuteronomy 34:6) to explain the two divine demonstrations of loving-kindness that frame the Torah? What is the relationship, in your view, between the importance that rabbinic tradition places on preparing the dead for burial and God’s burial of Moses in this parashah?

- Read “Unfulfilled Promise” by Merle Feld, in Voices (p. 1288).

- Who is the speaker in the poem’s first five stanzas and in the last stanza?

- What was the speaker’s vision of what the Promised Land would look and feel like? How does her confidence and faith in her “scout” enable her to make this journey?

- How do you imagine the speaker feels as she listens to the words of her “steady guide” in the poem’s sixth and seventh stanzas?

- How does the speaker feel in the poem’s last stanza? How does this help you understand how the Israelites might have felt upon Moses’ death? Do you recall a time in your life when you had similar feelings? What gave you the confidence to go ahead into the “wasteland”?

Overarching Questions

As you study these parts of the parashah, consider the following overarching questions. If time permits, conclude the study session with these broad questions:

1. Can you think of a time in your own life when you received a blessing, or what felt like a blessing, from an older relative, a teacher, a mentor, or some other respected individual? What was it like for you to receive this blessing? What impact did this blessing have on your life?

2. The biblical text tells us that at the time of his death, Moses’ “eyes were undimmed and his vigor unabated” (Deuteronomy 34:7), although he was 120 years old (the ideal human lifespan, according to Genesis 6:3). How does this description of Moses at the end of his life compare with the way in which our society views the elderly? What can we learn from the way the text describes Moses about how we can live full and vigorous lives as we age?

Closing Questions

1. What new insight into the Torah did you gain from today’s study?

2. What other new insights did you gain from this study?

3. What questions remain?