Parashat B’chukotai Study Guide Themes

Theme 1: We Get What We deserve . . . Don’t We?

Theme 2: What’s it Worth to You?

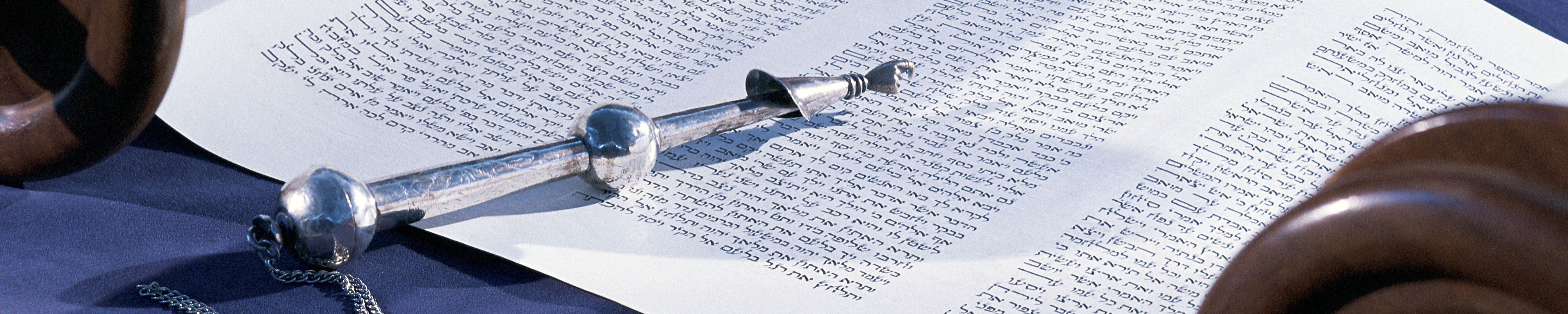

INTRODUCTION

Parashat B’chukotai brings the book of Leviticus to a close. The primary concern of Leviticus is the Israelites’ proper behavior in its most important manifestations: between one individual and another, and between an individual and God, in the home and in the sanctuary. B’chukotai addresses the question of how the Israelites—God’s chosen people—are to be motivated to ensure adherence to God and God’s law. This question is particularly timely because the people are at a momentous point in their desert sojourn: soon they will leave Mount Sinai and embark on their trek to the Promised Land. The society to be built there will be based on God’s commandments, which have been painstakingly transmitted to Moses since the journey from Egypt began. Without Moses, who will die before the people cross the Jordan River, the Israelites will lose their direct connection to the eternal. Thus God’s law will be only as valuable and efficacious as the people’s ability and willingness to follow it. This parashah makes the case for a rather straightforward equation: obedience will result in divinely granted reward, while the outcome of disobedience will be God’s wrath. The particulars of reward and wrath are clearly delineated in B’chukotai, and this study guide invites participants to bring their own ideas about reward and punishment to the “conversation.”

The end of the portion, in an appendix-like format, concerns the treatment of the sanctuary, God’s dwelling place among the people. Instructions about the maintenance of this structure and the proper offerings to be brought to it conclude the portion and this book. The last sentence, “These are the commandments that the Eternal gave Moses for the Israelite people on Mount Sinai” (Leviticus 27:34), links the instructions in this section with the original Sinai meeting between God and Moses, thus reinforcing their import, their value, and their magnitude.

BEFORE GETTING STARTED

Before turning to the biblical text and the questions presented below, use the introductory material in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary to provide an overview of the parashah as a whole. Draw attention to a few key quotations from the introduction to the Central Commentary on page 765 and/or survey the outline on page 766. This will allow you to highlight some of the main themes in this portion and give participants a context for the sections they will study within the larger parashah. Also, remember that when the study guide asks you to read biblical text, take the time to examine the associated comments in the Central Commentary. This will help you to answer questions and gain a deeper understanding of the biblical text.

THEME 1: WE GET WHAT WE DESERVE . . . DON’T WE?

Blessings and threats (significantly more of the latter than the former) are presented here as the consequence of either obedience to God’s commandments on the one hand or neglect or defiance of God’s mitzvot on the other hand. These commandments pertain to both women and men; and some of the commandments that are specific to women provide the reader with important information about female life in biblical society. Blessings and curses will touch the full scope of life—fertility and barrenness, harvest and famine, health and sickness, wealth and poverty, building and destruction, peace and warfare, and finally—and most terrifying—divine abandonment of the people, at least until they turn back to God. This section presupposes an orderly world in which events will unfold purposefully and as promised; there should be no surprises. Several commentators challenge the premise that there are direct consequences to following, or not following, God’s commandments. Participants too will have the opportunity to consider the limits of the assertion explicated in this theme, which questions the idea that we really get what we deserve.

- Read Leviticus 26:3–13. What are the rewards and blessings that God promises the people in return for their faithfulness? How would you characterize the nature of these rewards and blessings overall?

- Note the order in which the rewards are enumerated. Why do you think these rewards are arranged in this way? If you were asked to rank them in order of importance to you, what would the order of your list look like? What values would be implicit in your organization of the blessings?

- Read Deuteronomy 7:13–14, a parallel blessing to Leviticus 26:9, as well as the commentary to Deuteronomy 7:14 on page 1092. Both blessings represent fertility as divinely given. Why do you think that infertility in the Bible is almost always inflicted on a woman and not a man? What might this suggest about the attitudes and assumptions toward women and God’s relationship with them?

- What, if anything, would you add to this listing of blessings? What would you eliminate, if anything?

- Read the Central Commentary to the first halves of Leviticus 26:11–12 on page 768. Why do you think that the promise of these particular blessings is couched in such a literal form? What does this suggest about the Israelites’ needs? What event in the people’s recent history can you recall that suggests that they need such a tangible relationship with their God?

- The blessings are listed in ten verses (Leviticus 26:3–13), while the curses take up more than three times as many verses (vv. 14–45). Read Leviticus 26:14–29. Hearing these curses, what feelings do you imagine would have been evoked for the Israelites? What feelings are evoked for you when you read threats enumerated in these verses? Both the blessings and the curses sections make clear that the standard of behavior is the people’s adherence to God’s commandments. Why do you think there are so many more curses than blessings, and why are the curses more detailed?

- Compare the first curse (Leviticus 26:14–16) to the first blessing (vv. 4–5). What is the relationship between these two divine promises? Next compare the blessing in verse 6 with the curse in verse 17, and, finally, the blessing in verse 9 and the curse in verse 20. In looking at these sets, what other symmetries or parallels do you notice? How do the essential themes in each set reflect the most profound human needs and fears? How do you respond to the basic premise of this part of the parashah, that people are rewarded or punished based on their actions? Do you think that people get what they deserve?

- Read the Central Commentary on Leviticus 26:26. According to Hilary Lipka, what does this verse reveal about women’s responsibilities in the Israelite community at this time? Why is this particular curse so devastating?

- In many parts of the contemporary world, individuals who have domestic responsibilities such as food preparation are considered to be of low social status. The lists of blessings and curses reveal a great deal about the structure of Israelite society. Where do you imagine that domestic work fell on the scale of social status in biblical times? Why would it have been the primary responsibility of women? From these lists, what do you think were the roles of highest status, and why were these positions so important?

- Lipka cites other ancient Near Eastern curses similar to the one in Leviticus 26:26. Why do you think one finds such similarities in the literature of these various groups?

- In the Central Commentary to Leviticus 26:29, Lipka discusses cannibalism. What does she convey about the social order by raising the specter of cannibalism? Why do you think that this curse immediately follows the one before it? What is the relationship between these two curses?

- Read the Contemporary Reflection on pages 782–83. Sarah Sager notes “something profoundly unsettling” about this parashah. What is the theological dilemma to which Sager is referring? How does she explain biblical scholar Nehama Leibowitz’s understanding of the blessings and curses enumerated in B’chukotai?

- What does Sager suggest about the relationship between “God’s Creation and humankind’s responsibility,” particularly with regard to the moral order to the universe? According to Sager, when in the Divine-human encounter did this relationship first become truly manifest? What was the action that set in motion, as Sager describes it, “the process of Revelation”? What was significant about the encounter in Genesis 18:25?

- In the last paragraph of the Contemporary Reflection, Sager states, “There is no quid pro quo for individuals in the world. . . .” At first glance, this statement appears to be at odds with the text found in Leviticus 26:14–45, in which the consequences of unfaithfulness are so powerfully described. What is Sager’s understanding of this section of the parashah, and how does she use it to reconcile these two positions? How does this relate to our theme that we get what we deserve? What is your perspective on this issue?

- In “You Are Wondrous” on page 784, Lea Goldberg writes that “by law” she is not entitled to the joy she feels. How does this poem relate to the blessings and curses described in this parashah? How do Goldberg’s words challenge the message of the biblical text?

- There are limitless ways to experience feelings of joy or happiness. What are the ways in which Goldberg experiences her “happiness” in this poem?

- Can you think of a time in your life when “happiness caught [you] like a downpour”? What was the source of your happiness and in what ways was it manifest to you?

- How is the “happiness” that Goldberg experiences related to the theme of this section of the parashah that good is rewarded and evil punished? does it fit with the message of the parashah, or is it in opposition?

THEME 2: WHAT’S IT WORTH TO YOU?

This theme covers a particularly provocative part of B’chukotai. The sanctuary was to be supported through an assortment of gifts and dedications including the opportunity to pledge the equivalent in shekels of one’s own self. This section categorizes Israelites on the basis of age and gender and assesses their values accordingly. By extension, this part of the parashah challenges the student to consider the many ways that human beings are identified and valued, not just by gender and age but by sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and race as well.

- Read Leviticus 27:1–8 and the Central Commentary on pages 774–75. According to the Central Commentary, what was a “[vow] to YHVH” (v. 2)? What were the roots of this practice? What could be pledged? Who made vows? Under what circumstances would a person be likely to make such a vow? Who/what benefited from the vow and how?

- Review the monetary equivalents of pledges to the sanctuary according to gender and age. According to Carol Meyers, in the introduction to Leviticus 27:1–8 on page 774, what are some possible explanations for the age and gender differences noted here?

- Read the Central Commentary on Leviticus 27:4–7 on page 775. According to the shekel equivalency for men and for women, what was a woman’s relative economic worth in each of the four age groups? In which group was a woman’s value greatest? The lowest? What were the factors that had an impact on the valuation at each age level?

- In the Another View section (p. 780), Carol Meyers argues against the conventional view, implicit in the biblical text, that the disparities between male and female values in votary pledges reflect a view of women as inherently less worthy. What is Meyers’s contention? What is the difference between “labor potential” and “intrinsic worth”? Do you find Meyers’s argument convincing? Why or why not?

- In Post-biblical Interpretations, read the first comment on Leviticus 27:2 (pp. 780– 81). What are the possible meanings of the Hebrew noun ish? According to Charlotte Elisheva Fonrobert, what did the Rabbis in Mishnah Arachin 1:1 understand ish to mean in Leviticus 27:2?

- In this section, Fonrobert gives a number of examples of women making vows in Mishnah Arachin. What were they? What makes most of these vows thematically similar? What might this reveal about the role of women in biblical society? About the possible predispositions of the authors of these texts? How are these texts related to the issue of the inherent worth of men and women delineated in Leviticus 27:3–7?

- In the second comment on Leviticus 27:2 (“the equivalent for a human being” [p. 781]), Fonrobert notes that dedications could no longer be made to the Temple once it was destroyed. Yet the Rabbis devoted considerable effort to the formulation of several Mishnaic tractates on the subject of oaths and vows. What is Fonrobert’s explanation for their doing so in the absence of the Temple? According to this theory, how did the use and meaning of vows evolve as the circumstances of Jewish life changed?

- According to the comment on Leviticus 27:4 on page 781, what were the tumtum and the androginos? What was their status on the scale of human valuation? What were their limitations, and in what ways were they equal to those with a less-ambiguous sexual identity?

- The issue of sexual variation (homosexuality, transgender, bisexuality, etc.) is a hot- button topic today. What are the implications of the rabbinic thinking demonstrated in Mishnah Arachin for our own times? How might this rabbinic mind-set be used to reframe, understand, and constructively address these issues when they arise in our own communities?

- Read “That Very Night” in Voices on page 785. How does the speaker of the poem “become” a man? What physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual differences does she/he now experience? How do “all the words I’ve written till now” change in her newly masculine eyes? What does the poem say to us about the difference in worth between words spoken by a man as opposed to those of a woman? How does the central message relate to the biblical text’s valuation of men and women?

- In “Packing Slip” on page 786, how does the list of personal qualities used to describe the author compare to the list in Leviticus 27:3–4? What do you think the author might mean when she writes, “Contents, which may have settled during living, contain live cultures”? What are the “contents”? What are “live cultures”? Construct a “Packing Slip” for yourself. What is on your list? What are your “live cultures”?

- Read “Nearing 80” on page 786, which has been connected to Leviticus 27:7. In the biblical verse, who appraises the value of the sixty-year-old man or woman? Where is the voice of the sixty-year-old herself? In the poem, who makes the assessment of the author? How does the author confront the calendar, and what is the outcome of their “confrontation”? What would your “Nearing 80” poem say about you?

Overarching Question

As you study these parts of the parashah, keep in mind the following overarching question. if time permits, conclude the class with these broader question:

- How much control do human beings have over their lives and their fate? What options are at our disposal to increase control over our own destiny?

- How do you “assess” yourself? What are the criteria you use to do so? Have these criteria changed over time? If so, what do you think has accounted for the change?

- How do you define productivity? What are the various ways to measure and evaluate one’s worth to one’s community? to one’s family? to one’s self?

Closing Questions

- What new insight into the Torah did you gain from today’s study?

- What other new insights did you gain from this study?

- What questions remain?