Parashat B’midbar Study Guide Themes

Theme 1: Making it Count

Theme 2: If Elected, We Will Serve—Making the Levites Count

INTRODUCTION

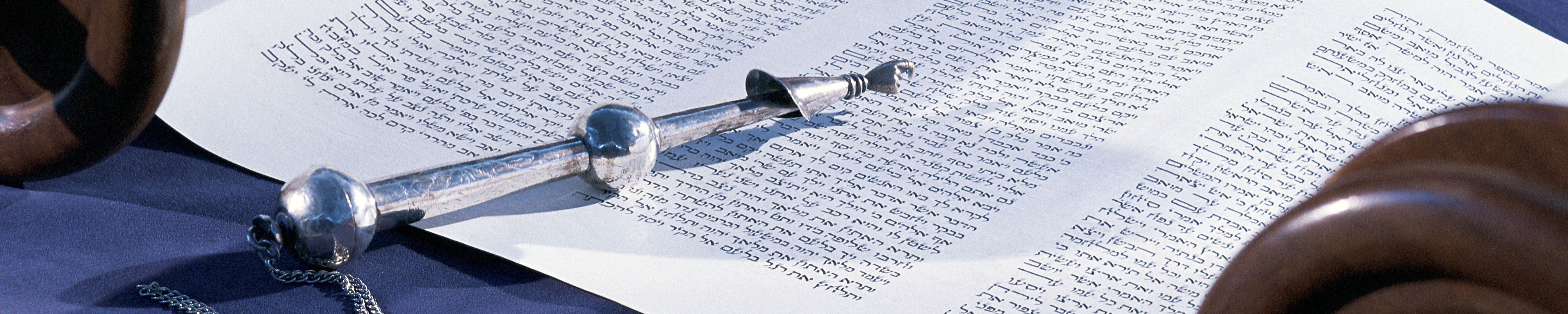

Parashat B’midbar, the first Torah portion in the book of Numbers, describes the Israelites’ forty-year journey from Mount Sinai to the steppes of Moab—the people’s last stop before entering the Promised Land. The divergence between the English and Hebrew names of this fourth book of the Torah highlights the daunting tasks confronting the Israelites on their way to peoplehood. the book of Numbers—and this parashah—begins with a description of the census that God commands Moses and Aaron to take of men eligible to fight. The Israelites are more than a year into their journey from Egypt; they have received God’s laws and constructed a Tabernacle (Mishkan). Organizing eligible men into fighting battalions is necessary in order to prepare to enter Canaan, an area inhabited by nations with their own armies. To become a nation capable of claiming and ruling the Promised Land, the Israelites will need to be counted and organized as a nation of warriors. The Hebrew name of the book of Numbers, B’midbar (“in the wilderness [of]”), reflects the period of transition between servitude and life as a free people. The Israelites are in a process of wandering—both literally and figuratively. They are on their way to Canaan, learning how to live according to God’s expectations, while at the same time taking stock of themselves in the wilderness—a place without an existing structure. To ensure space for encounters with the divine during their journey and beyond, the people must organize the community in a way that protects the Holy of Holies—the place of supreme sanctity at the center of the Tabernacle. God commands that the men of the tribe of Levi encircle the Tabernacle and attend the high priestly family, thus expanding the circle of those who conduct the rituals that ensure the community’s access to the Divine.

BEFORE GETTING STARTED

Before turning to the biblical text and the questions presented below, use the introductory material in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary to provide an overview of the parashah as a whole. Draw attention to a few key quotations from the introduction to the Central Commentary on pages 789–90 and/or survey the outline on page 790. This will help you highlight some of the main themes in this parashah and give participants a context for the sections they will study within the larger portion. Also, remember that when the study guide asks you to read biblical text, take the time to examine the associated comments in the Central Commentary. This will help you answer questions and gain a deeper understanding of the biblical text.

THEME 1: MAKING IT COUNT

God commands Moses and Aaron to conduct a census of eligible fighting men, those who will constitute the army that will conquer the Promise Land. The census reflects the centralization of authority in the emerging Israelite nation, for it creates a hierarchy in which some members of the community are included and some are excluded. The census also reinforces a patriarchal system in which power resides with able-bodied men.

- Read Numbers 1:1–4, which describes God’s command to Moses to take a census.

- How does God’s command to take the census (v. 2) conflict with the promise in Genesis 15:5 that the Israelites will be as numerous as the stars (“count the stars, if you can count them”)? What two ideas seem to be in conflict here?

- Who is to be counted in the census (Numbers 1:2)? Why were women excluded from this list?

- The term beit avot (“ancestral houses”) in verse 2 describes the core institution of the agricultural and tribal system of ancient Israel. What is the relationship between the beit avot and the tribes, according to the Central Commentary on this verse? What defines a particular beit avot? How does a beit avot differ from the larger clan and tribal units? In what ways does the beit avot determine the economic yield of a group? What is the impact of a woman’s marriage on the beit avot of which she is a member?

- What is the significance of the fact that “every male” should be counted in the census (v. 2)?

- The phrase tz’vaot . . . tzava (“groups . . . bear arms”) in verse 3 refers to the military roles carried out by men. How is the same root (tz-v-a) used in Exodus 38:8 to describe women? According to the Central Commentary on Numbers 1:3, what are other examples in the Bible of this root’s application to female service?

- How does verse 4 help you to understand the label of “tribe” in ancient Israel? What is the relationship, according to the Central Commentary on this verse, between the internal and external functions of a tribe?

- Read Numbers 1:5–19, which lists the names of the tribal representatives.

- The Central Commentary notes that the list of tribal chieftains is ordered according to their ancestral mothers (Genesis 35:22–26). in your view, what is the significance of this ordering in the list of tribes?

- Who is the tribal representative from Judah, according to Numbers 1:7, and what is his relationship to Aaron? What tribal alliance does the marriage of Elisheba and Aaron establish? What does this foreshadow, according to the Central Commentary on this verse?

- According to verse 18, how do Moses and Aaron organize the company of fighters after the census? According to the Central Commentary on this verse, how does the representation of the people of Israel as an army affect the women?

- The word translated as “who were registered” in verse 18, a form of the Hebrew root y-l-d, usually means “to give birth.” Here it is a self-reflexive form of the verb. How does this unusual use of the verbal root in this verse help you to understand the significance of the army’s creation?

- Compare the first verse of this parashah with verse 19. What is similar about these verses? How do these verses legitimize the census? How does this contrast with God’s reaction to taking a census in other places in the biblical text, according to the Central Commentary on this verse?

- The Israelites are on their way to becoming a nation. They have been liberated from Egypt, accepted the revelation of God’s Torah at Mount Sinai, and received civil and ritual laws. In your view, what does the formation of an army contribute to the process of forming their identity as a nation?

- Read the Another View section by Beatrice Lawrence, on page 808.

- According to Lawrence, what values are reflected in the principles that underlie Moses’ organization of the people?

- What is the relationship, in Lawrence’s view, between responsibility and access to the divine?

- How is patriarchy as a cultural system reflected in the way Moses organizes the people?

- According to Lawrence, what lesson can we glean from this parashah about a handful of important women? How does this parashah make a strong statement about the matriarchs of Israel?

- Read Post-biblical interpretations by Judith R. Baskin, on page 809 (“Adonai spoke to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai”).

- What connection does Midrash B’midbar Rabbah 1.2 make between Numbers 1:1 and Jeremiah 2:31?

- Who are the three mentors God assigns to Israel in the wilderness, according to this midrash, and what are their roles in sustaining the people?

- What were the particular characteristics of Miriam’s well during the Israelites’ journey?

- In your view, what is the significance of the Israelites’ experience in the wilderness for their formation as a nation? How do the resources God provides through Moses, Aaron, and Miriam assist the people—both physically and psychologically—in this process?

- Read the Contemporary Reflection by Rachel Stock Spilker, on pages 810–811.

- Stock Spilker notes that while the word adat (Numbers 1:2) is translated as “community,” it can also refer to an “assembly, band, company, or faction.” How does this nuance help us understand who is not counted in the census God commands Moses to take? What is the relationship between being counted in a census and how society views the worth of those groups who are counted?

- What are the dangers in taking a census, according to BT Yoma 22b?

- How does Rashi interpret the command to take a census? What does Rashi’s interpretation teach us, according to Stock Spilker?

- What are the dangers of counting members in our synagogues, according to Stock Spilker? How do our synagogues sometimes demonstrate that some members “count” more than others? How can we do a better job of making sure that all synagogue members and their families feel that they matter?

- According to Stock Spilker, what are some of the untold stories of the people that are missing from the biblical census? What do we miss by not knowing their stories?

- How do you relate to Stock Spilker’s statement that we are more than the sum total of our parts?

- What can we learn from who is missing from the “counting” in this parashah about what it means to count and to be counted?

- Read “Forgotten” by Lisa Levine, in Voices (p. 813).

- What does the poem’s protagonist wonder in the first half of the poem?

- What are the women in the poem doing while the men are being counted?

- What point does the speaker make by referring to herself as “the womb that held them”?

- To what extent do you relate to the speaker’s sense of being forgotten or excluded? Can you think of a time in your life when you experienced similar feelings?

- Read “They Had Names” by Susan Glickman, in Voices (p. 814).

- How does Glickman describe her relatives in the poem’s first two stanzas? How do you relate to these descriptions?

- What is the relationship between the stories these relatives told and the poet’s memories of these people? What is the significance of the information contained in these stories?

- What is the importance of knowing, for the poet and for ourselves, where we “fit” in “that long line of descendants from the country of the old”? How does knowing where we fit help us both to count and to be counted?

- Numbers 1:5 lists the “names of the representatives”—all of whom are men—who will assist Moses and Aaron in taking the census. What is the connection, in your view, between the poet’s list of her relatives’ names—which includes both men and women— and Numbers 1:5?

- What point does the poet make about our history—both as a people and as members of families? What is the relationship between these memories and our history, both as a people and as part of specific families?

THEME 2: IF ELECTED, WE WILL SERVE—MAKINGTHE LEVITES COUNT

According to God’s command, the Levites are not counted in the census. They are to become caretakers of the Tabernacle, its furnishings, and everything that pertains to it. The Levites will take down and set up the Tabernacle during the people’s journey; they are to encamp around it, standing guard so that “wrath may not strike the Israelite community” (Numbers 1:53). Although the Levites may not face the dangers of war, they are on the front lines in confronting the dangers of proximity to the holy.

- Read Numbers 3:1–10, which describes the election of the priests.

- How does the text describe the line of Aaron and Moses in verse 1? In your view, why does the text says that God spoke with Moses on Mount Sinai?

- According to the Central Commentary, what is deterministic genealogy, and how does verse 1 demonstrate the value that the priestly writers (who are thought to be the editors or authors of the first section of Numbers) placed on this concept?

- The verbal root m-sh-ch (“to anoint”) in verse 3 refers to Aaron’s sons (“anointed priests”). How does the meaning of this verbal root help you to understand the idea of anointing priests? According to the Central Commentary on this verse, for what reasons did people in the ancient Near East anoint themselves with oil? What is the meaning of the special verbal root used in this verse?

- What is the fate of Aaron’s sons Nadab and Abihu, according to verse 4? The biblical text describes their deaths in Leviticus 10:1–2. In your view, why are their deaths mentioned again in this verse?

- What is the role of the tribe of Levi in relation to Aaron, according to Numbers 3:6? What is the special position that the kohanim (priests) of the family of Aaron occupy within the tribe of Levi? How does this structure parallel that of the Tabernacle?

- How does the work the Levites are commanded to do (v. 7) reinforce the priestly hierarchy? In your view, what is the relationship between this hierarchy and who can have access to the divine?

- How does the danger associated with violating the rules of access to the tent of Meeting in verse 10 help you to understand the significance of the Levites’ function in the priestly hierarchy?

- Read Numbers 3:11–15, which describes how the Levites replace other first-born Israelites who would otherwise belong to God.

- In verse 12, how does the phrase “the first issue of the womb” differ from the term “first-born”? How does the description of the womb as the source of the child rather than the mother herself reflect on the text’s view of women’s reproductive agency?

- According to verse 13, what impact did the tenth plague, the killing of the first-born of Egypt, have on future generations of Israelite males? How does this passage change that situation? Why do you think this change was made?

- According to the Central Commentary on verse 13, what is the status of the first-born male in the Tanach? How does the struggle between Jacob and Esau (Genesis 25–27) reflect this reality?

- Read Numbers 3:40–51, which describes the price of God’s redemption of the Levites’ first-born.

- How do you understand the term “first-born”? According to the Central Commentary on verses 40–51, to whom does the term “first-born” apply in this parashah?

- What does God command Moses in verses 40–41? What additional command does God give Moses in verse 41 that is not in verses 11–13?

- How do you understand God’s command in verse 45 that “the Levites shall be Mine”? In your view, why must the Levites give up their cattle in order to serve God?

- What are the benefits to the priests who receive the redemption money God commands Moses to collect (v. 48)? in what ways does this command reinforce the priestly hierarchy?

- Read Post-biblical Interpretations by Judith R. Baskin on pages 809–10 (“But Nadab and Abihu died by the will of Adonai . . . and they left no sons,” “So it was Eleazar and Ithamar who served as priests in the lifetime of their father Aaron,” and “record every male among them”).

- Why do you think the Rabbis connect the deaths of Nadab and Abihu with their unwillingness to marry? What biblical verse does the midrash use as a proof-text for this view, and how does the midrash interpret this verse? What is your reaction to this interpretation?

- What do you think accounts for the Rabbis’ interest in how Aaron, Eleazar, and Ithamar shared their priestly duties? What views of the priesthood, and of the mothers of priests, does B’midbar Rabbah 2.26 express? How does this midrash reflect rabbinic society’s views about the behavior and role of virtuous women?

- What question does Numbers 3:15 raise for you (and for the Rabbis)? How did the Rabbis answer this question? What are your reactions to the ways in which the Rabbis addressed the absence of women in this verse? According to Baskin, how did Rabbinic Judaism, while valuing males over females, recognize the importance of women?

OVERARCHING QUESTIONS

As you study these parts of the parashah, keep in mind the following overarching questions. If time permits, conclude the class with these broader questions:

- Women do not appear in parashat B’midbar. Women are not counted in the census, nor do they have a role to play in maintaining and protecting the Tabernacle. Can you think of a time in your life when you were excluded from the Jewish community? What contributed to that exclusion? What was your reaction to being excluded? In your view, perhaps informed by your personal experience, how can we include those in the Jewish community who have, traditionally, been marginalized or excluded?

- In this parashah, God charges the Levites with protecting that which is holiest—the Tabernacle. What is holy to you in your life? In what ways do you protect that which is holy to you?

CLOSING QUESTIONS

- What new insight into the Torah did you gain from today’s study?

- What other new insights did you gain from this study?

- What questions remain?