Parashat Haazinu Study Guide Themes

Theme 1: The Many Faces of Israel’s God

Theme 2: God and Israel—The Arch of a Relationship

Introduction

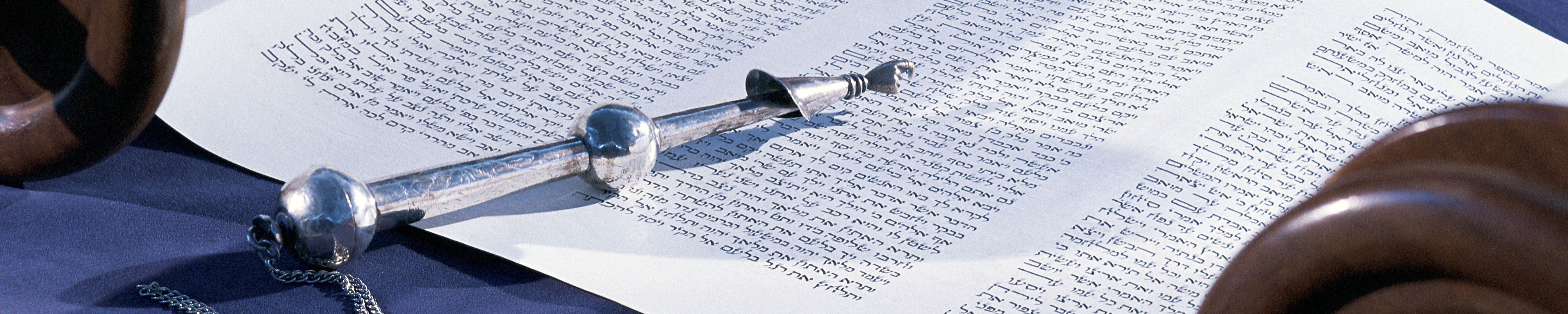

Parashat Haazinu, the next to last parashah in the Torah, fulfills God’s instruction for Moses to “write down this poem and teach it to the people of Israel” (Deuteronomy 31:19). This reflects God’s concern that after Moses’ death the Israelites will worship other gods and as a result incur God’s punishment. The poem traces the trajectory of God’s relationship with the Israelites, in good times and bad, and looks toward a future where Israel’s enemies will be vanquished. The poem that comprises much of Parashat Haazinu exhibits the core elements of biblical poetry, such as poetic parallelism, terseness, and various forms of repetition and patterning; in addition, one of its noteworthy features is its diverse metaphors for God. After the poem, Haazinu ends with God’s instructions to Moses about his imminent death. Moses will see the Promised Land from Mount Nebo, but God will not permit him to set foot in it. Parashat Haazinu reminds the Israelites that while human leaders are vital to their endeavor, they must prepare to be without the man who has guided them since they left Egypt; ultimately, it is only God and God’s instruction that endure.

Before Getting Started

Before turning to the biblical text and the questions presented below, use the introductory material in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary to provide an overview of the parashah as a whole. Draw attention to a few key quotations from the introduction to the Central Commentary on pages 1251–52 and/or survey the outline on page 1252. This will help you highlight some of the main themes in this parashah and give participants a context for the sections they will study within the larger portion. Also, remember to take the time to examine the comments in the Central 2 Commentary associated with the biblical text we are reading. This will help you answer questions and gain a deeper understanding of the biblical text.

Theme 1: The Many Faces of Israel’s God

The poetic language of Haazinu contains diverse and striking metaphors for God that invite us to think about the vastness of God’s roles in the universe. These images include depictions of God as a natural element (Rock), a bird (eagle), an avenging warrior, and a parent both loving and stern (explicitly a father and a mother who gives birth to and nurses her child, Israel). Haazinu portrays divine emotions of nostalgia for God’s early relationship with Israel, anger at Israel’s insubordination, and determination to vindicate and protect the people. These metaphors paint a textured, rich, and compelling portrait of Israel’s God.

- The word tzur (rock) is a keyword in this parashah, recurring eight times. In five cases (Deuteronomy 32:4, 15, 18, 30, 31), tzur refers to the God of Israel.

- Read each of these five verses, and compare how this divine metaphor operates in these passages. What aspects of God’s nature does the word tzur highlight in these passages? According to the Central Commentary by Andrea L. Weiss on verse 4, to what type of rock does this word refer?

- The metaphor of God as a rock is used elsewhere in the Bible. For example, in the book of Psalms, the psalmist cries out to “my rock and my redeemer” (Psalm 19:15) and praises “my strength . . . my fortress, my rescuer, my God, my rock in whom I seek refuge” (Psalm 18:2–3). What aspects of God does the word tzur highlight in these verses?

- The metaphor of God as a rock is found in the prophetic texts of the Bible as well. For instance, in 2 Samuel 22:47, we read “YHVH lives! Blessed is my Rock! Exalted be God, the Rock.” In Isaiah 26:4, the prophet exclaims, “For in Yah YHVH you have an everlasting Rock.” Isaiah 30:29 describes God as “the Rock of Israel, on the Mount of YHVH.” What qualities about God do these verses suggest?

- How does the metaphor of God as rock in Psalms and the Prophets compare to its usage in Deuteronomy 32?

- In what ways do these varying uses of this metaphor reflect your own views of God?

- The word av (father) is used in Deuteronomy 32:6 to refer to God, one of only twelve times the word is used in the Hebrew Bible in this way.

- Read verse 6 and the Central Commentary on this verse. How does the metaphor of God as parent differ from metaphors that describe God as shepherd, king, or master?

- What aspects of God does this paternal metaphor for God express? Why do you think this metaphor is particularly important for this poem?

- Read Deuteronomy 32:11–12, which refers to God as an eagle.

- What qualities make an eagle a fitting metaphor for God?

- What images does the word translated here as “rouse” (‘-v-r) suggest?

- According to the Central Commentary, what is another interpretation of the word “rouse”? How have observations by ornithologists influenced the interpretation of this verse?

- Compare the image of God spreading wings in this verse with the similar image in Exodus 19:4. How do these images compare with the description of how God carries Israel in Deuteronomy 1:31?

- How does the metaphor of God as an eagle compare with the prior metaphor of God as a rock?

- Read Deuteronomy 32:13–18, which contains female images of God.

- The verbal root y-n-k (to nurse, suck) in verse 13 adds a maternal image to that of God as father (v. 6). What does this communicate about the way God provided for the Israelites once they entered the Promised Land?

- Verse 18 contains another maternal divine metaphor. How does the metaphor in verse 18 compare with the image in verse 13? In the later context, what message about God does this metaphor aim to communicate?

- What are the differences between y’lad’cha (begot) and the verb h-y-l (labored), the two words that describe God’s creation of the people in verse 18? Why do you think the poet selected an explicitly maternal metaphor for God in verse 18 instead of a paternal image? What does the text express about the connection between God and Israel by selecting this language?

- To what extent does the image of God as a mother reflect aspects of your own experience of the Divine?

- Deuteronomy 32:25–27 introduces the metaphor of God as a (male) warrior, a metaphor that continues in verses 41–43.

- What aspects of God’s nature does this metaphor highlight? What messages about God does this image help communicate?

- According to Carol Meyers (see Central Commentary on Deuteronomy 32:23 and on Exodus 15:3), what can we learn from the images of God in these verses about whether the composers of the Torah viewed God as a male being?

- How does this metaphor compare with those examined above?

- Read Post-biblical Interpretations by Judith R. Baskin, on page 1266, “Like an eagle who rouses its nestlings” and “You neglected the Rock who begot you / Forgot the God who labored to bring you forth.”

- How does Sifrei D’varim 314 use the metaphor of God as an eagle rousing its nestlings (32:11) to evoke the image of the Shechinah?

- According to this midrashic text, to what other divine redemptions of Israel does 32:11 allude?

- How does Sifrei D’varim 319 use the idea of a male giving birth to give extra weight to God’s love of Israel?

- Read the Another View section by Julie Galambush (p. 1265).

- What are some of the “startling contradictions” about God’s facets that this parashah asks us to confront?

- According to Galambush, what was the role of female and male warrior gods in ancient Near Eastern culture? How did this differ in Israelite culture?

- How is the image of God as a warrior-king tempered in this parashah?

- Read the Contemporary Reflection by Ellen M. Umansky (pp. 1267–68).

- What troubles Umansky about the various contrasting images of God in this parashah? How does her response to these metaphors compare with your own?

- What does Umansky suggest makes modern readers uncomfortable with how commentators interpret the metaphor of God as a rock in this parashah?

- What disturbs Umansky about the image of God as a warrior?

- How do feminists suggest that we re-imagine our relationship with God through the use of different images of God?

- How does your understanding of God change based on some of the nonanthropomorphic images of God that contemporary theologians such as Marcia Falk and Judith Plaskow employ? What is your reaction to these approaches?

- Which metaphors for God in this parashah resonate with you? Which do you find challenging? To what extent did these metaphors prompt you to think about God in new ways?

- Read “My People” by Else Lasker-Schüler, in Voices, on page 1269.

- How does the image of the rock in the poem’s first line compare with the metaphors of God as a rock in this parashah?

- What is the relationship between the crumbling rock and the “songs of God” in line 3?

- What seems to be the poet’s view of why she has “plunged from the path”?

- To what might “shuddering eastward” (line 11) refer?

- What is the relationship, in this poem and in the parashah, between “enduring on the land” (Deuteronomy 32:47) and living according to “all the terms of this Teaching” (32:46)?

Theme 2: God and Israel—The Arch of a Relationship

Parashat Haazinu tells the story of God’s relationship with the Israelites—from its hopeful beginnings after the Exodus, through the dark days of Israel’s worship of foreign deities and God’s desire to punish the people, to God’s reconsideration of punishment. The poem’s use of vivid metaphors and its powerful descriptions of divine emotions highlight the intensity of the relationship between God and Israel over time. It is a relationship shaped by a complicated history of love, betrayal, anger, and forgiveness. As the Israelites prepare to enter the Promised Land, Shirat Haazinu reminds them that their relationship with God is the foundation of the way forward into this new life.

- Read Deuteronomy 32:4–14, which describes God’s early relationship with Israel.

- What is the nature of the relationship between God and Israel described in the second half of verse 6? What is the meaning of the verb k-n-h (created you) in verse 6 in the context of God’s relationship with Israel? Why do you think there are three different verbs in this verse that describe how God begot Israel?

- According to verses 7–8, what did God do in “the days of old”? What are the variant readings for verse 8, and how do they alter your understanding of this verse?

- What does verse 10 suggest about the condition of the people when God “found them” in the wilderness? The Central Commentary connects this verb to the language found in Hosea 9:10 and Ezekiel 16:3–6. What do these two passages suggest about the imagery that may lie behind our verse?

- According to the Central Commentary, what is the meaning of the phrase “as the pupil of God’s eye” in Deuteronomy 32:10?

- What does the image introduced by the words “to feast” (v. 13) add to your understanding of the early relationship between God and Israel?

- According to the Central Commentary on verses 13–14, with what kinds of foods did God feed Israel? What do these foods represent, and what is their significance in the relationship between God and Israel?

- Read Deuteronomy 32:15–18, which describes the people’s ingratitude and how their worship of foreign gods anger God.

- How do the verbs in the first half of verse 15 (“grew fat and kicked,” “grew fat and gross and coarse”) describe Israel’s response to the generous provisions with which God provides them? What images do these verbs evoke?

- What are the offenses with which God charges the Israelites in this passage?

- To what does the word sheidim (demons) refer in verse 17? The same word is used in Psalm 106:37 to describe how the Israelites adopted the ways of their Canaanite neighbors and “sacrificed their sons and their daughters to the demons.” How does the use of this word in Psalm 106:37 shape your understanding of the word usage here?

- Read Deuteronomy 32:19–25, which describes God’s proposed punishment for the Israelites’ transgressions.

- What consequences will befall the people for their insubordination?

- What does the repetition of the two verbs in verse 21 indicate about how God plans to respond to the people’s transgressions?

- How does the repetition of the word “no” in this passage emphasize the relationship between Israel’s transgressions and God’s reaction?

- What is the impact of the inclusion of female and male, young and old in the consequences promised in verse 25?

- Read Deuteronomy 32:26–31, which marks the poem’s turning point from God’s vow to punish the people to a desire to protect them from their enemies.

- In verses 26–28, what reasons does God give for reconsidering punishment for the people’s transgressions?

- How does the poetic parallelism of “thousand . . . ten thousand” (v. 30) amplify the meaning of these verses?

- Read Deuteronomy 32:39–43, which describes how God will avenge Israel’s foes.

- How does verse 39 confirm the monotheistic view of a single deity? How does this compare to sections of the Torah that suggest an acceptance of the existence of other gods? (See Central Commentary to Deuteronomy 4:35.)

- What are the contrasting aspects of God’s nature in verse 39? Compare this verse to the depiction of God in Isaiah 45:6–7: “I am YHVH and there is none else, I form light and create darkness, I make weal and create woe—I YHVH do all these things.”

- How do scholars view the original version of Deuteronomy 32:43? How does it differ from the version in our translation? Why might scribes have removed one of the lines?

- How does God’s early relationship with Israel (described in Deuteronomy 32:4–14) contrast with God’s attitude toward the people in verses 19–25? What are the reasons for this change? What do you think accounts for God’s desire to protect the people (vv. 26–31)?

- What can this parashah teach us about our own relationships? How does the arch God’s relationship with Israel parallel the long-term relationships in our own lives? What can we learn from the trajectory of the relationship between God and the Israelites in this Torah portion about how we might respond when someone fails to live up to our expectations of them?

- Read “Journey’s End” by Linda Pastan, in Voices, on page 1269.

- How does the poet use the metaphor of a journey to describe how we live our lives?

- Why, according to Pastan, do we live our lives in this way?

- How does the parental imagery in the poem’s second and third lines compare with the parental images of God in this parashah?

- What does the poet suggest is the consequence of treating our years “like stops along the way of a long flight from the catastrophe we move to”?

- In your view, what is the impact on our relationships of living life so that we “reach death safely”?

Overarching Questions

As you study these parts of the parashah, keep in mind the following overarching questions. If time permits, conclude the class with these broader questions:

1. Parashat Haazinu uses a variety of metaphors to describe God and portrays God in the human-like roles of father, mother, and warrior. In what ways do metaphors help you to understand and relate to God? What do you think accounts for the human need to describe God in such terms?

2. How has a significant relationship in your life changed over time? What have you learned about yourself, about others, and about life looking back over the arch of this relationship?

Closing Questions

1. What new insight into the Torah did you gain from today’s study?

2. What other new insights did you gain from this study?

3. What questions remain?

Explore Jewish Life and Get Inspired

Subscribe for Emails