Parashat Vayeilech Study Guide Themes

Theme 1: Into the Crystal Ball: A View of the Future

Theme 2: Whose Story Is It Anyway?

Introduction

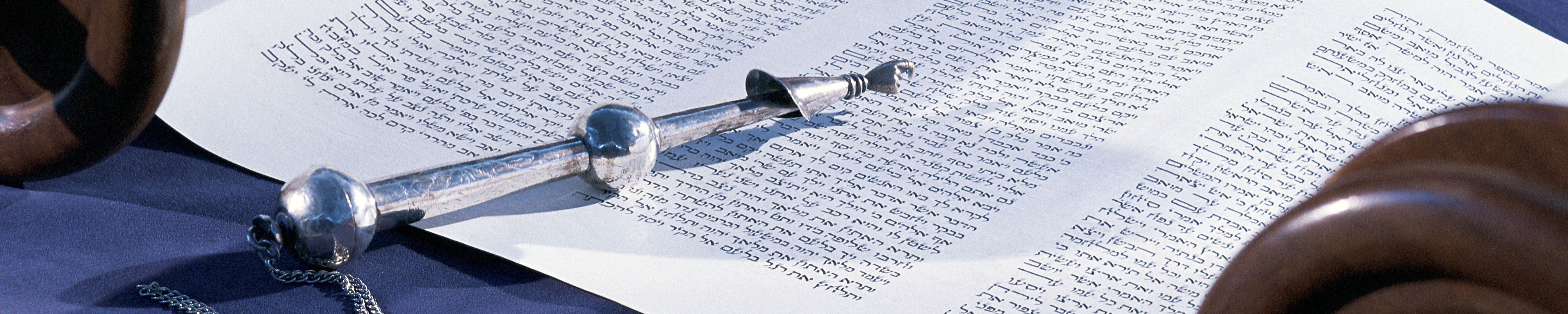

This portion, the briefest in the Torah, takes place at a pivotal moment in the Israelites’ desert sojourn. After almost forty years of oral communication—God to Moses, Moses to the people—the spoken word is converted to written text. This momentous act—securing a foundational text for generations to come—occurs at an encampment on the steppes of Moab. Moses’ death is imminent. In one of his last acts as their leader, Moses calls upon the Israelites to accept Joshua as his successor and provides them with the written word that is to guide their personal and communal lives. One of the most striking aspects of this parashah is the mixed message delivered as Moses and God forecast the Israelites’ future. Their words vary from encouraging and supportive to deeply pessimistic and determined: the people will succeed and thrive; the people will stray and fail. Although the written word is secured—in the form of a Teaching (torah) and a poem (shirah)—neither Moses nor God believes that the newly written texts will guarantee the ongoing loyalty and compliance of the people. On a more encouraging note, however, the call to the people to “hear and learn” (Deuteronomy 3:13) is an inclusive one. There are no age limitations, no gender restrictions. Adults and children, residents and strangers are all included. Not only that, these Teachings are meant for generations to come as well, even those “who have not had the experience” (31:13), who did not know Moses and who never lived at a time when God addressed a human being face-to-face.

Before Getting Started

Before turning to the biblical text and the questions presented below, use the introductory material in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary to provide an overview of the parashah as a whole. Draw attention to a few key quotations from the introduction to the Central Commentary on pages 1235–36 and/or survey the outline on page 1236. This will allow you to highlight some of the main themes in this portion and give participants a context for the sections they will study within the larger 2 parashah. Also, remember that when the study guide asks you to read biblical texts, take the time to examine the associated comments in the Central Commentary. This will help you to answer questions and gain a deeper understanding of the biblical text.

Theme 1: Into the Crystal Ball: A View of the Future

In this section, first God and then Moses forecast and delineate the various ways that the Israelites will fail once they enter the Promised Land. The people will be attracted to and will follow alien gods. Although initially they will prosper, they will forget the One who made it possible for them “to eat their fill and grow fat” (Deuteronomy 31:20). Their defiance and stiff-necked nature will lead them only to sin and evil. The outcome of their wicked ways is predictable: misfortunate will surely be their fate.

- Read Deuteronomy Deuteronomy 31:1–6.

- When Moses addresses the Israelites in verse 2, the English translation renders Moses describing himself as no longer capable of being active. According to the Central Commentary on verse 2 by Adriane Leveen, what is the literal translation of the Hebrew in this verse? What different associations are suggested for you between this more literal translation and the translation that appears in the text? How does each translation affect your understanding of Moses’ physical and/or mental condition?

- Moses seems to attribute his inability to enter the land to his own physical limitations as opposed to it being a punishment. When he acknowledges that God told him he could not cross the Jordan, he does not remind the people why God made this decision. How do you account for the difference between the way Moses recasts the past and the way these events appear earlier in the Torah? Why do you think Moses chooses to present the situation in this manner? In the Central Commentary to verse 6, Leveen notes the repeated use of the divine injunction to the people, “Be strong and resolute.” This expression is used three times: by Moses to the people (verse 6), by Moses to Joshua (verse 7), and by God to Joshua (verse 23). What do you think is the reason each speaker said these words to their intended audience? Why do you think this particular expression was chosen? What underlying challenges does it suggest? If you were responsible for crafting such a message of encouragement, what would it be?

- Read Deuteronomy 31:14–16.

- Read the Central Commentary to verse 16, “alien gods.” Which “alien gods” does God refer to here? Why do you think that God predicts that the people will turn to them? What human tendencies might suggest that this will happen? Can you think of another time during their forty-year desert sojourn that the people behaved similarly? What was the outcome?

- In the Central Commentary to verse 16, Leveen discusses the expression “go astray after,” which more literally means “go whoring after,” used in describing God’s prediction that the Israelites will shortly turn to “alien gods.” Turn back to Numbers 15:39 to read a similar divine injunction. According to Leveen, numerous biblical 3 texts use prostitution as a metaphor for adultery and apostasy. What do turning to other gods and adultery have in common? How do you feel about the use of this expression to describe the Israelites’ predicted wrongdoing?

- Leveen notes that the relationship between God and Israel is often described as a marriage, with God as the husband and Israel as the wife. In what ways is the relationship between God and Israel similar to the relationship between a husband and wife? How is it different? How does this metaphor enhance or hinder your understanding and appreciation of the covenantal relationship? What alternative symbolism might you use to depict this relationship?

- Read Deuteronomy 31:16–21.

- In these verses God makes specific threats to the Israelites in anticipation of their evil behavior. What are these threats?

- Which threat do you think might be most effective as a “scared straight” technique? Which one would frighten you the most and why?

- Can you recall a time in your life when you were threatened by a parent or caregiver? What was the nature of the threats, and what was the impact of them on your future behavior? Were the threats effective? Why or why not? As a parent or caregiver yourself, do you ever issue threats? If so, what motivates you to do so? Do you think they are effective? Why or why not?

- According to the Central Commentary on verse 19, why does God instruct Moses, “Therefore, write down this poem and teach it”? According to Leveen, what are some of the different interpretations of the purpose of the poem? Which explanation do you find more compelling? What other interpretation of God’s order can you suggest?

- What is God’s list of indictments against the people? What, specifically, does God predict that the Israelites will do, both in deed and attitude?

- Imagine that you are standing with the Israelites on the verge of entry into the long-awaited Promised Land. What would you be feeling? Imagine that you hear God’s bleak prediction as conveyed by Moses. What value do you think there might be in the text’s emphasis on this bleak prediction? Now imagine receiving a more optimistic forecast about your upcoming behavior. How would each version affect you, and what might be the impact of each one on your future actions?

- Read the Another View section by Talia Sutskover on p. 1245.

- Despite God’s pessimistic assessment of the Israelites’ future, Sutskover depicts Moses as devoting great care and attention to preparing the people for his impending separation from them. According to Sutskover, what are the various ways in which Moses demonstrates his “love and devotion”?

- What does Sutskover suggest will be the impact of Moses’ inclusive stance on the Israelite community in the future?

- What metaphor does Moses use in Numbers 11:12 to describe his relationship with the Israelites? How might this conception of the relationship benefit the people as they go forward without him?

- When in your own life have you had to “go forward” without a key protective figure (such as a parent, a spouse or partner, a sibling, or a particularly cherished friend)? What aspects of the relationship were you able to draw on to help you “go forward”?

- Read the Contemporary Reflection by Elaine Rose Glickman on pp. 1247–48.

- According to Glickman, what is the contradiction between Moses’ explanation for not going with the Israelites into the Land and the Torah’s earlier explanation given in Numbers 20:12?

- Given that Moses knows his fate has already been determined by God, why do you think that in this parashah he first attributes it to his age and insufficient energy?

- Glickman discusses the role of choice (and the absence of choice) in how human beings live their lives. In your reading of verses 16–21, how does choice function in the Israelites’ future behavior? That is, do they have a choice? Can they exert free will, or is their fate already determined? If so, what are the conditions or circumstances that will direct their future?

- Glickman writes, “Today, we like to make our own choices. . . . We can choose the life we want to live—except when we cannot.” How much control do you feel you have been able to exercise in your own life? What combination of personal qualities and circumstances accounts for the degree of control that you possess? What constrains you? Do you think you can challenge and overcome these constraints? If so, what would you need to do to make that happen?

- Read “The Keepers of My Youth” by Karen Alkalay-Gut in Voices on p. 1249.

- In this poem, the author writes about some significant adults from her childhood who are now near the ends of their lives. What is the connection between Alkalay-Gut’s description of these elderly people and Moses’ self-description in Deuteronomy 31:2? How do these descriptions differ?

- In the poem’s last paragraph, what role does the poet take? How does she interact with “the keepers of [her] youth”? How does her stance toward “[her] troops at the front” compare with that of God in Deuteronomy 31:16–21, both of whom are “whisper[ing] farewells” to people about to set out on a momentous journey?

Theme 2: Whose Story Is It Anyway?

Every story is colored by the experiences, perspectives, and values of its author. Thus, no history is ever “pure” or incontrovertible. In Deuteronomy 31:9, we read, “Moses wrote down this Teaching.” As such, this communal memoir, narrated by a lone man, is forever linked to him. As important as the manifest content of the written text itself is an awareness of the perspective—and distortions—created by the gender, age, and social status of its author. Theme 2 invites participants to consider the purposes, functions, and limitations of a written document, in the biblical story and in their own lives. This section of the study guide also raises questions about what a Torah written by a woman might have been like. What parts of the story would be similar and what parts different? What would matter, and what would be considered insignificant? How might Jewish history have been changed if a woman had authored a record of it?

- Read Deuteronomy 31:7–13.

- Read the Central Commentary to verse 9. According to Adriane Leveen, what are the various meanings of the Hebrew word torah? Which meaning of torah does verse 9 refer to?

- What does Moses do with the Teaching when he has finished writing it? What instructions does he give regarding its future use, and to whom does he give them?

- Read the Central Commentary to verse 10. What reason does Leveen suggest for the annual reading of the Teaching at Sukkot? Why does verse 11 explicitly state that the document must be read aloud?

- According to verses 12–13, who must hear the annual reading? Why do you think the text specifies that these individuals must listen to and learn from the annual recitation of the Teaching? What message can you draw from these verses about the torah?

- Read Deuteronomy 31:16–30.

- According to the Central Commentary to verses 22 and 24–27 (p. 1243), what is the poem (shirah)? How does it differ from the Teaching (torah)? In what ways are the two works similar? How are they different?

- Read the Central Commentary to verse 19. What two interpretations does Leveen present here regarding the function and purpose of the poem?

- Why was it critical at this juncture in the Israelites’ history to convert an oral text to a written one?

- In verses 24–27, Moses finishes writing down the Teaching and then addresses the Israelites. What is his mood and outlook in this short speech? What might be the connection between Moses’ completing the work that will represent him after his death and his subsequent anger and despair?

- In her comment on Deuteronomy 31:9, Leveen notes, “Later biblical books speak of the torah of Moses. . . . Thus the Teaching (torah) of Moses provides guidance and an anchor for Israel.” Today we routinely refer to the Torah as “the Five Books of Moses.” So, going forward, this foundational Jewish text is forever linked with one individual, its putative author, Moses. With this in mind, return to the introductory material of the parashah to consider the following questions posed by Leveen (p. 1235):

- What are the repercussions of having the tale narrated by a single dominant male voice, that of Moses?

- What if, instead, the story was to be told from the perspective of a female figure, such as Miriam? What might a female narrator have considered crucial if she were asked to retell the events of the wilderness journey?

- What vision of community might she propose?

- If you had been given the opportunity to write the story of the nascent Israelite nation as a Teaching (torah) for the generations to come, what would you have considered to be most important to include? What would be least important?

- In Post-biblical Interpretations by Meira Kensky, read the commentary on verses 31:12, 31:24, 31:26, and 31:30 on pages 1246–47.

- In her comment on 31:12 (“Gather the people . . .”), Kensky notes that while the Rabbis did not challenge the inclusivity of the command to hear the divine Teaching, the medieval interpreters felt otherwise. Using the same verse, what distinction between men and women did Rashi make? What conclusions did the Tanna D’Vei Eliyahu draw from this verse? What was Nachmanides’ disagreement with the Tanna?

- Deuteronomy 31:24 serves as a basis for the ongoing debate about the Torah’s authorship. In rabbinic writings, what are the two basic hypotheses about its writer, and what are the essential arguments for each?

- In her comment on verses 26 and 30, Kensky points out that verse 26 mentions “this book of Teaching,” and shortly after that, in verse 30, Moses recites the words of “the poem.” How did some of the Rabbinic and medieval commentators attempt to resolve uncertainty about the relationship between the two texts?

- Regarding the poem, how did some commentators interpret it as being used as an indictment against Israel, while others believed its purpose was to defend Israel?

- Read “What We Need” by Elaine Marcus Starkman in Voices on page 1250.

- According to the poet, what do poems offer women that “depressions, holidays, lovers, prayers, friends” cannot? What link might there be between your answer to this question and God’s instruction to Moses to write down a previously oral text?

- Why do you think the poet links “immersing minds” with “losing our bodies”? Why might the latter be a prerequisite for the former?

- In the poem’s last line, the author mentions “our hunger.” To what might that hunger refer?

- The author suggests that poems can offer “an enormity, “grace,” “sanctity,” and “delicious worth” to the hungry reader. Have you ever felt yourself to be a “hungry reader”? What were you “hungry” for? What felt unfulfilled? What writings (poetry, prose, memoir, sacred texts) have provided you with nourishment? Have these sources of emotional or spiritual nourishment changed during your life? If so, what were they in the past, and what have they become now? What changes do you imagine might occur in the future?

- Read “The Old Prayer Book” by Miriam Ulinover in Voices on page 1250.

- How would you summarize the story the poet tells about her grandmother? What impression does the poem give as to what type of woman the grandmother was? Does she resemble any women you know?

- The author writes about boys who would hit a young girl in kheder. How does this depiction contrast to the divine instruction in Deuteronomy 31:12?

- What does the poet imply when she states, “A girl’s voice yowling can carry high as heaven”?

- What does the poet mean in the line, “But therefore a young wife is put in an ample chain, with the same old prayer book, only now without a pointer”? What is the “ample chain”? What is the significance of being “without a pointer”?

- How does the siddur (prayer book) function in this poem as the author’s grandmother’s “childhood home”? Have any sacred texts provided you with a “childhood home”? If so, what were they? What did they mean to you, and what role(s) did they play in your life, both in childhood and in adulthood?

Overarching Questions

As you study these parts of the parashah, keep in mind the following overarching questions. If time permits, conclude the class with these broader questions:

1. Who is the author of your story? That is, who shaped the memories, values, and recollection of events that form your history?

2. Under what circumstances is an oral story most valuable? When is a written document preferable?

3. Should communal stories always be authored by a community member? What is the impact of having military history written by the victors, the stories of a minority community written by a member of the dominant culture, or men writing about the lives of women?

Closing Questions

1. What new insight into the Torah did you gain from today’s study?

2. What other new insights did you gain from this study?

3. What questions remain?