Parashat Matot Study Guide Themes

Theme 1: “I Give You My Word”: Promises Kept and Promises Compromised

Theme 2: “Your Fate Is In My Hands”: Children Sacrificed and Children Saved

Introduction

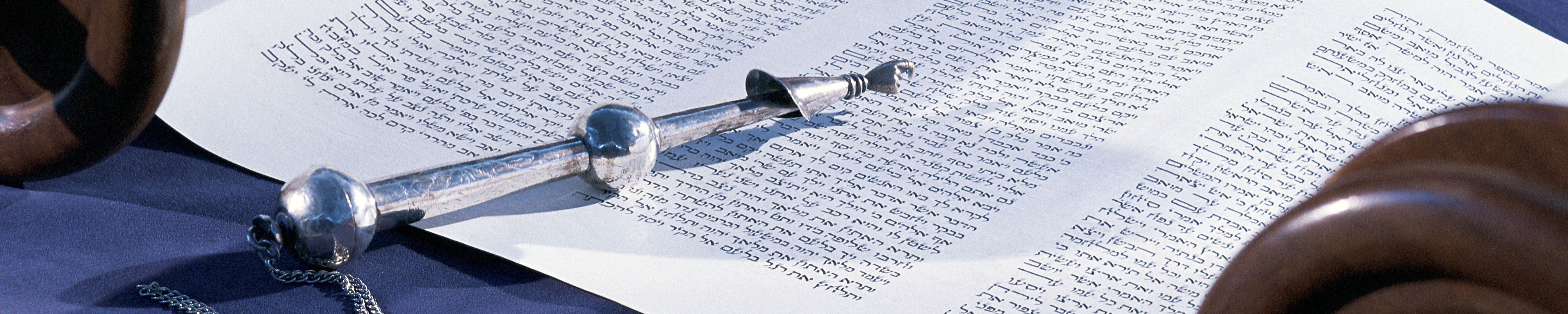

In this portion, Moses continues to prepare the Israelites for life in the Promised Land, a life that they will have to navigate without him. Parashat Matot reflects Moses’ understanding that in the future the community’s challenges will come from both within and without. In order to successfully establish themselves as a sovereign nation, the people will need to be able to defend themselves from the threats of other nations while also maintaining stability and peace among themselves. Overcoming the threats from their enemies will require physical prowess on the battlefield. On the other hand, meeting the dangers from within will require not physical but interpersonal capabilities, including the ability to keep one’s word. To make a vow or oath was an act of utmost seriousness and significance in biblical times. In this portion, Moses explicates the particulars of vowing as transmitted to him by God.

Before Getting Started

Before turning to the biblical text and the questions presented below, use the introductory material in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary to provide an overview of the parashah as a whole. Draw attention to a few key quotations from the introduction to the Central Commentary on page 989 and/or survey the outline on page 990. This will allow you to highlight some of the main themes in this portion and give participants a context for the sections they will study within the larger parashah. Also, remember that when the study guide asks you to read biblical text, take the time to examine the associated comments in the Central Commentary. This will help you to answer questions and gain a deeper understanding of the biblical text.

Theme 1: “I Give You My Word”: Promises Kept and Promises Compromised

The instructions to men who make vows are brief: once a man has voiced a pledge, he has taken upon himself an obligation that must be fulfilled. The text makes clear that women, too, made vows and oaths in biblical times. However, significant gender differences characterize the act of making and carrying out such pledges. While there appear to be no restrictions on men, there are significant constraints on women. Age and marital status are the major determinants of a woman’s right to fulfill any promises she might seek to make.

- Read Numbers 30:2–3.

- To whom are the vows and oaths mentioned in verse 3 made? Read the Central Commentary by Elizabeth Goldstein on verse 2, “Introduction” on page 991. What is the meaning of the Hebrew word matot, the name of this parashah? How does an item belonging to an individual, as used in Genesis 38, function as a symbol of its owner’s status?

- Read the Central Commentary for verse 3 on page 992. What is a vow? What is an oath? What are the similarities between them, and what are the differences?

- Now turn ahead and read Deuteronomy 23:22. What do we learn from both verses about the power of vows and oaths and the seriousness of making them?

- Read Numbers 30:4–10.

- From reading these verses, what general assumptions can you make about women and vows/oaths in the biblical period?

- Read the Central Commentary at the bottom of page 992, “A Woman’s Vows and Oaths.” According to Goldstein, what was most likely the primary concern of the biblical writers regarding the impact of women’s vows? In addition to the vowing woman herself, who else was likely to be affected by these promises?

- Read the Central Commentary to verse 4, “assumes an obligation” on page 993. What does the Hebrew term actually mean? What are positive obligations, and what are negative ones? According to author Carolyn Bynum, quoted in this comment, how could women’s vows of self-denial impact others besides herself? Who might these others be? How would the actions of such a woman enlarge her sphere of influence and power?

- Verses 4–6 describe some specific conditions of vows made by women. What is the status of the women described here? What are the possible constraints on them? Under what specific circumstances may their vows be annulled and by whom? What are the limitations on these women’s fathers’ ability to constrain them? If her vows are cancelled, what will be God’s response?

- According to Goldstein’s comment verse 4, “while still in her father’s household,” who potentially stood to benefit from the vows of an unmarried woman residing in her father’s home? Who stood to lose?

- Verses 7–9 describe the extent and limitations on the vows of newly married women. 3 How are these conditions similar to those on the women described in verses 4–6? How are they different?

- In both cases described above, what do you think is the significance of limiting fathers’ and husbands’ ability to annul vows to just the one day on which they learned of them?

- How do the rights of the women discussed in verse 10 compare to those described in the previous verses?

- Read Numbers 30:11–17.

- According to the Central Commentary on verse 13, what is the significance of the phrase “crossed her lips”? How might a married woman use this as a technicality, a loophole, or a way to creatively bypass communally accepted limitations on her autonomy?

- Verse 14 introduces a further specification of obligations, those that involve “selfdenial.” The Central Commentary translates the Hebrew to mean “to afflict the person” and suggests possible forms for such affliction in biblical times. Are there times in your life when you “afflict” yourself? If so, when are those times? What is the reason for your actions, and what is the impact of your taking them? On yourself? On others? Do you accord anyone else in your life the right or privilege to cancel or otherwise undo your decisions?

- Read Post-biblical Interpretations by Dvora E. Weisberg on pages 1006–7.

- Commenting on Numbers 30:2, Weisberg quotes Rabbi Moses Sofer’s explanation of why the biblical text has Moses specifically addressing communal leaders about “promises and commitments.” What do you think of Rabbi Sofer’s comment? What other reason(s) might there be for why Moses’ comments were directed to the communal leaders?

- Regarding Numbers 30:4, Weisberg cites BT N’darim 79a–b, 81b–82a. How would the acts of self-denial listed in this talmudic text impact not only women themselves but those around them? Regarding the latter, what motivation might women have had for swearing off personal adornments and other “pleasures”? What might this imply about women’s power and their ability to use it both directly and indirectly?

- Regarding Numbers 30:9, Weisberg explains that in the N’darim text, a husband’s ability to veto his wife’s vows is limited to her vows of self-denial or to those that would affect the marital relationship. By contrast, the biblical text presents no limitations on a father’s or husband’s ability to annul a daughter’s or wife’s vows as long as he acts on the day he learned of the vow. What do you think might have accounted for this constriction of male privilege and control over women’s lives by the talmudic era?

- What rights, if any, do you think one spouse should have with regard to vows his or her spouse makes that directly impact him or her?

- Read the Contemporary Reflection section by Jacqueline Koch Ellenson on pages 1008–9. Koch Ellenson notes that to protect her vows from being annulled, the young or married woman in biblical times might have had to either make no vow at all or make one in silence, thus violating established protocol. Koch Ellenson writes, “She acts by pretending that she 4 has not acted. . . . She must betray herself to be true to herself.” In thinking about your own life, have you ever kept silent “to be true to [your]self”? What were the circumstances? At the time, what did you think would be the consequences had you spoken out? What were the costs of keeping silent? Looking back, would you handle the same situation differently now? If you would, what would account for the change?

- Read “I’ll Drop My Plea,” by Rivka Miriam in Voices, page 1010.

- When you read this poem and speculate about the nature of the poet’s “plea,” what possibilities occur to you? If you were writing a poem about a “plea” of yours, what would the plea be about or for?

- The poet writes that she can no longer “carry” her plea. Why do you think this is? What might be contained in her plea, that she must contemplate such an action?

- What might be so powerful about the poet’s “secret,” whispered to her plea, that “out of fear” the plea retreats, “seals itself up”?

- In the middle of the poem, in a new image, the writer describes her plea as sticking and clinging to her. Why do you think she attributes this situation to “dread” and “fear”?

- The poem begins with the writer’s decision that she will drop her plea but ends with her asking, “How can I drop it?” How might such a tension be resolved? What resources or help might be at the poet’s disposal that she does not yet see or cannot yet imagine

- Read “Kol Nidrei, September 2001,” by Grace Schulman.

- The author writes that “main clauses,” “syllables,” “verbs,” “sentences,” “images,” and “penciled lines” have all been rendered useless or impotent. What do these things represent, and why does the author link them to the cancelled vows?

- What is the author’s “court”? Why is there no ark, benches, prayer shawls, holy books, or ram’s horn in this poem? Where have they gone? Why have they been replaced by “only trees”? What makes this a sanctuary for the author, even without the traditional accoutrements?

- According to the writer, why are “all vows” cancelled after September 2001? If you were the author writing this poem nine years after “Kol Nidrei, September 2001,” do you think your perspective would be the same, or would it have changed? If you think it would have been different, in what ways, and what do you think would account for the change?

Theme 2: “Your Fate Is In My Hands”: Children Sacrificed and Children Saved

Parashot Matot presents the laws of vowing in theoretical form; there is no narrative about these matters in this portion. However, later in the Bible, in the section known as Prophets (N’vi-im), two powerful and dramatic stories take vowing as their central theme, and the reader has the opportunity to see the playing out of this section of Matot in the lives of real human beings. In the first story, from the Book of Judges, in the early days of Israel’s settlement in Canaan, a man named Jephthah is chosen to lead the Israelites in battle against the hated Ammonites. Invoking God’s help in the upcoming struggle, Jephthah “vowed a vow,” which would demonstrate his gratitude should he prevail in battle. The second tale, from the First Book of Samuel, also involves a military challenge. In this story, King Saul calls upon his people to abstain from 5 eating, an “offering” to God in return for victory in battle. Both men’s vows have potentially catastrophic consequences for their own children, outcomes not foreseen or considered by either father. One story ends in tragedy, another in salvation. Both afford the reader a thought-provoking opportunity to consider the “prescriptive” materials from Matot in the broader context of the subsequent Israelite narrative.

- Read Judges 11:30–40, the story of Jephthah and his daughter. Then read I Samuel 14:24–45, the story of King Saul and his son, Jonathan.

- What did Jephthah ask God for, and what did he vow in return if his plea was granted?

- What was Jephthah’s reaction when he came to his home in Mizpah? What was his daughter’s response when she learned of his vow? Why do you think that Jephthah’s daughter responded as she did?

- According to the biblical text, how was the daughter of Jephthah remembered after her death? By whom was she remembered?

- What was King Saul’s vow? What did Jonathan do, and why did he do it?

- What was Jonathan’s response when he learned of his father’s promise?

- How did the community respond to Saul when they learned of his plan for Jonathan? What was the outcome?

- Why do you think the biblical authors of this text chose to note Saul’s child’s name but not Jephthah’s? What inferences might be drawn from this decision, and how does this affect your understanding of these stories?

- Read the Another View section by Tamara Cohn Eskenazai on page 1006.

- Both biblical tales involve impulsive promises made by fathers and the disastrous, or potentially disastrous, consequences of their actions for their children. In the biblical text, fathers have the right to annul the vows of their daughters or wives under certain conditions. What do you think about the fact that, as shown in the Jephthah and King Saul stories, men could make vows regarding their children without restraint, restriction, or oversight by another person? In your view, under what circumstances, if any, should one person have the right to countermand the vows of another? If the vow will affect only the vower? If the vow will significantly affect the life of someone else? Never?

- Eskenazi writes that “the stories of Jephthah’s daughter and of Jonathan also convey messages about community and protest.” What do you think about the fact that communal “protest” results in Jonathan’s being saved from his father’s vow but not Jephthah’s daughter? Significant gender differences occur in these stories. In the first, both the victim and the protestors of Jephthah’s vow were women; in the second, both were men. What might this suggest about the relative power of men and women to countermand or undo dangerous promises made by reckless individuals? About women and men as the potential victims of others’ vows? Can you think of examples from contemporary life in which gender differences are a significant factor in the ability of groups of people to protest wrongdoing or outright evil?

Overarching Questions

As you study these parts of the parashah, keep in mind the following overarching questions. If time permits, conclude the class with these broader questions:

1. In comparison to biblical times, how do you think vows and oaths are thought of in contemporary times? How do you think about them?

2. In our world today, what would be the advantages of taking vows and oaths as seriously as they are taken in the Matot text? Are there disadvantages to doing so?

3. In your own life, have you ever made what you would consider to be a very serious vow or oath or promise? If you did, what were the circumstances? Why did you feel that a vow was necessary or appropriate? Did you fulfill it? If you did not, what was the reason? What was the result? If you had the opportunity now to replay what happened, would you make different choices?

4. Although vows or oaths may be made by an individual, other people are often affected by them. Under what, if any, circumstances, do you think that those others so affected should be able to challenge or even annul an individual’s pledge? What criteria would you choose to guide your decision?

Closing Questions

1. What new insight into the Torah did you gain from today’s study?

2. What other new insights did you gain from this study?

3. What questions remain?