PARASHAT VAYEITZEI STUDY GUIDE THEMES

Theme 1: The Journey Cycle of Biblical Heroes

Theme 2: From Barrenness to Fertility

Theme 3: Rachel Stole the Household Gods

INTRODUCTION

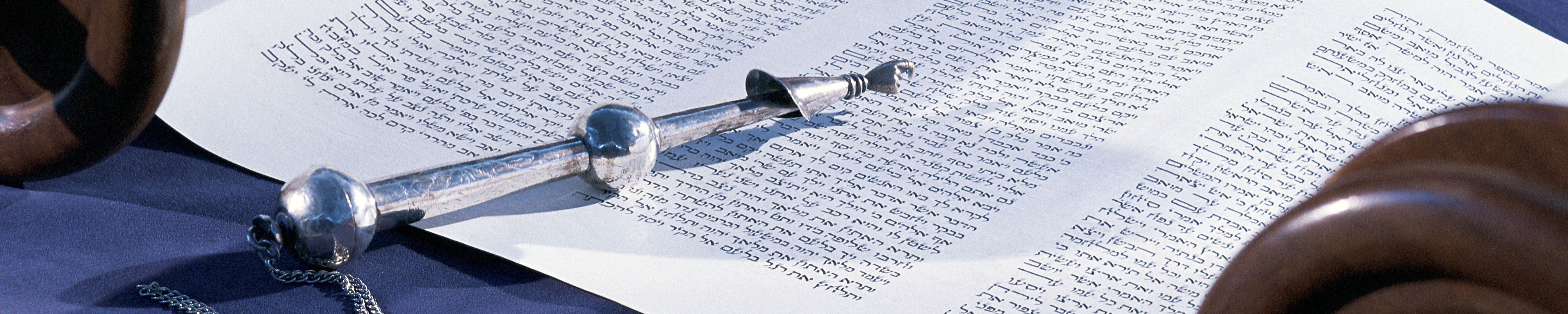

Parashat Vayeitzei (“he went out”) focuses on the third generation of the biblical patriarchs and matriarchs, Jacob, Rachel, and Leah, as well as their maids Zilpah and Bilhah. in the previous parashah, Parashat Tol’dot, Jacob tricked his father, Isaac, into giving him Esau’s birthright. Now, at the outset of our parashah, Jacob flees his home and heads towards Haran, the homeland of his mother, Rebecca.

Parashat Vayeitzei chronicles Jacob’s journey away from his home in Canaan, the beginning of his formal relationship with God, the formation of his own complex family in Haran, and his ultimate return to his homeland. Major themes that recur in Parashat Vayeitzei include the journey of biblical heroes, the transition from barrenness to fertility, and Rachel’s theft of her father’s t’rafim.

SUGGESTIONS FOR GETTING STARTED

Before turning to the biblical text and the questions presented below, use the introductory material in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary to provide an overview of the parashah as a whole. Draw attention to a few key quotations from the introduction on p. 157, and survey the outline on p. 158. Note that the outline highlights repeated themes, such as the trope of heroes’ journeys and the competition between women and men. There are also certain progressions in the parashah, such as the shift from competition between sisters to sisterly collaboration and the movement away from home, to a temporary home, to finally finding a permanent home. understanding where the study guide theme you are focusing on fits within the larger parashah will help contextualize your learning.

THEME 1: THE JOURNEY CYCLE OF BIBLICAL HEROES

In her introduction to Parashat Vayeitzei (p. 157), Rachel Havrelock observes, “the stories of Rachel and Jacob illustrate the distinct but intersecting male and female journey cycles that characterize Genesis 12–35.” She contrasts the male journey cycle of the patriarchs with the female journey cycle of the matriarchs. According to Havrelock, the male protagonists in Genesis embark on a transformative journey that involves several stages: the “hero departs from home, gains intimacy with God by wandering promised and unpromised lands, has visions while exposed in the outdoors, and struggles to fulfill God’s blessing by engendering children.” For the female heroes of the Genesis narrative, however, the “journey toward intimacy with God takes place in the internal terrain of the body” as the matriarchs struggle to conceive the children who “shall be like the dust of the earth” (Genesis 28:14). the questions below explore how Havrelock’s observations play out in this particular parashah.

- Read Genesis 28:10–22, which recounts the initial encounter between Jacob and God.

- What does Jacob’s dream involve? What do you think this vision represents?

- What type of relationship does this episode establish between Jacob and God?

- How does Jacob respond to the dream?

- How might this dream be a symbol of Jacob’s own journey?

- How would you characterize Jacob’s character given thus far?

- Read Genesis 29:9–18

- What characteristics are given about each of the future matriarchs, Rachel and Leah, when they are introduced?

- The text provides a few clues to the fact that Jacob thinks Rachel is special before he voices his desire to marry her in 29:18. What are some of those clues?

- Rachel Havrelock notes in her introduction to this parashah (p. 157) that the early lives of Rachel and Jacob are parallel. How are the two characters similar? How might this parallelism affect the relationship between them?

- Read Genesis 29:31–35.

- How is God involved in Jacob’s children’s conception?

- How do the names provide insight into God’s role?

- How do you compare Leah’s struggle to bear children to Jacob’s story?

- What, if anything, about Leah’s actions seems heroic to you?

- Read Genesis 30:1–8.

- How does Rachel react to her apparent inability to bear children?

- What names does she give the children born to Bilhah, her maid, and why?

- How do you react to her actions?

- What, if anything, seems heroic to you about Rachel’s actions?

- In her Another View essay (p. 176), Tammi Schneider challenges the notion that the biblical account favors Rachel over Leah. What evidence does she cite to support her claim that “the deity sympathized with Leah”? Do you agree with her conclusions about Leah? Why or why not?

- In Malka Heifetz Tussman’s poem “At the Well” (p. 180), whom do you believe is speaking? What leads you to that conclusion? How does your reading of the poem change if you view Jacob or Rachel as the speaker? 8. in your opinion, who is the hero of this story? On what do you base your response?

THEME 2: FROM BARRENNESS TO FERTILITY

A large portion of this parashah concentrates on the birth of Jacob’s children to Leah, Rachel, Bilhah, and Zilpah. The sisters differ greatly in their relationship with Jacob and in their ability to conceive and bear children. An examination of the narrative around the children’s birth provides insight into the sisters’ individual identities, their relationships with Jacob, and their relationships with God. Note that the entire birth sequence takes 46 verses (Genesis 29:31–30:24) and thus plays a central role in the parashah.

- Read Genesis 29:13–28.

- What deal do Jacob and Laban make?

- How does Laban demonstrate his power over Jacob despite his apparent joyous greeting?

- Rachel Havrelock notes with regard to Laban switching Leah for Rachel on the wedding night, “the provocative question that arises from this bed-trick is the same as that raised by Rebekah and Jacob’s earlier deception of Isaac: does human subterfuge disrupt the divine plan—or advance it?” (p. 163). In what ways is the deception in this episode similar to the deception witnessed when Jacob disguises himself as his brother, Esau, and steals his father’s blessing (Genesis 27)?

- Read the comment on Genesis 29:25 in the Post-biblical interpretations section (pp. 176–177).

- How does the midrash in Eichah Rabbah explain how the deception was executed?

- How do the Rabbis understand the relationship between Rachel and Leah?

- Read Sherry Blumberg’s poem “Leah to Her Sister” (p. 181).

- What emotions does the poet fill in to explain Leah’s actions in the story?

- How are these emotions different from the ones imagined by the Rabbis?

- Which of these two explanations do you prefer and why?

- How do you envision the relationship between Leah and Rachel?

- Read Rivka Miriam’s poem, “The Tune to Jacob Who Removed the Stone from the Mouth of the Well” (p. 180).

- In Rivka Miriam’s poem, what does Leah experience when she is given to Jacob?

- How does Leah compare herself to Rachel?

- According to this poem, what can Leah ultimately offer to her husband Jacob, who was tricked into marrying her?

- Read Genesis 29:31–35.

- What does God do to intervene in the relationship between Jacob and Leah? What reason does the text give for this intervention?

- What does Leah name her sons? How do these names show her acknowledgment of God’s role in their birth?

- Rachel Havrelock notes, “Rachel’s infertility becomes doubly bitter in the shadow of Leah’s celebrations of the births of her first four sons” (p. 165).

- What do the texts reveal about Rachel’s reaction to her infertility?

- What new information does this provide about the relationship between the sisters?

- Read the post-biblical interpretation of Genesis 29:29 (p. 177).

- According to Rashi, who are Bilhah and Zilpah?

- Why is it important that they be related to Rachel and Leah?

- Read Shirley Kaufman’s poem “Leah” (p. 181).

- According to this poem, what emotions does Leah experience as Jacob’s wife and mother of his children?

- How does the view of Leah in this poem compare to your perception of Leah based on the biblical text?

- How does the depiction of Leah in Shirley Kaufman’s poem compare to the way Leah is portrayed in the poems by Sherry Blumberg and Rivka Miriam?

- Read Genesis 30:1–13.

- How does Rachel react to her apparent difficulty in conceiving a child?

- In her comment on Genesis 30:1, Rachel Havrelock notes, “in effect, she protests not only the state of barrenness but also the limits that her society sets on female autonomy” (p. 165).

- Explain Havrelock’s statement—how is Rachel protesting her inability to have children and her limited power as a woman?

- How does Rachel’s statement, “Let me have children; otherwise I am a dead woman!” voice these two complaints that Havrelock lays out?

- Read the post-biblical interpretations to Genesis 30:1 (p. 177).

- According to the Rabbis, why does Rachel approach Jacob with this request despite the general acknowledgment by the family that God is the ultimate power in conception?

- Read the commentary by Isaac Arama, cited by Dvora E. Weisberg in the Post-biblical interpretations, in which he defends Jacob’s terse response to Rachel’s plea for children (comment on Genesis 30:1, p. 177).

- According to Arama, why is Jacob short with Rachel?

- What does this say about how Arama sees women in his own community or in the world he was familiar with? Is this consistent or inconsistent with the parashah’s overall understanding of women’s roles in biblical society? Why or why not?

- In Genesis 30:3–4, Rachel gives her maid, Bilhah, to Jacob in order to have children born in her name, just as Leah gives Zilpah when she is no longer bearing children (Genesis 30:9–10).

- What names do Rachel and Leah give these children? How do these names reflect their understanding of God’s role in the birth?

- What does Rachel offer as the reason she has taken this action?

- At this point in the narrative, what is the current state of the relationship between Rachel and Leah?

- Rachel Havrelock notes, “In the biblical narrative, birth is a moment of female collaboration when the boundaries between distinct bodies collapse, an occasion in which multiple female bodies operate in tandem” (p. 166). How does the biblical text support Havrelock’s suggestion that women collaborate in order to allow births? Do you see anything that suggests the woman are not working collaboratively?

- Read Genesis 30:14–21. this is the first time we see the sisters interact directly with one another.

- Both Rachel and Leah have something the other lacks. What are those things? How can your gauge their importance to the biblical writer?

- What do you believe is the state of the relationship between the two sisters at this point in the story? What specific parts of biblical text support this conclusion?

- Rachel Havrelock states, “The turning point in the sisters’ relationship comes with their readiness to enter into an exchange—to give each what the other lacks” (p. 167).

- What does Havrelock understand to be the state of the sisters’ relationship before this transition? What is their relationship after this change?

- How does her assessment compare to yours?

- Read Genesis 30:22–24, in which God remembers Rachel, and she conceives and bears a child. Rachel Havrelock writes, “In the stories of barren women, the occasion of divine remembrance signals that their actions have led to acknowledgment—and the reversal of their situation” (p. 168).

- What does Rachel say upon the birth of her son? Who does she believe is responsible for his birth?

- Is Rachel satisfied? Explain your answer.

- How does Rachel’s satisfaction relate to Havrelock’s proposition that once a barren woman conceives her actions have been acknowledged by God?

THEME 3: RACHEL STOLE THE HOUSEHOLD GODS

After Jacob’s children have been born, he prospers in his work for Laban. Jacob grows his own flocks as well as his father-in-law’s. As a result, Laban and his sons begin to begrudge Jacob his wealth, saying, “Jacob has taken all that belongs to our father; it is from our father’s possessions that he has gained all this wealth!” (Genesis 31:1) Given Laban’s mindset, God tells Jacob to return to his homeland. Rachel and Leah, realizing their lot is cast with their husbands, agree with Jacob’s assessment of the situation and leave Laban’s camp in secret while he is away shearing his sheep. in the midst of this activity, Rachel steals her father’s t’rafim. This section will explore what the t’rafim are, what we can learn about Rachel from her actions, and how Rachel’s interactions have been interpreted throughout history.

- Read Genesis 31:1–3, 11–16.

- What reason does the text provide for Jacob’s decision to return to his homeland?

- Note Rachel and Leah’s response to Jacob’s description of the situation (31:14–16).

- What reasons do they provide for their willingness to leave?

- What in the text gives you insight into the sisters’ relationship with each other? What about their relationships with their father and their husband?

- Read the first paragraph of Wendy Zierler’s Contemporary Reflection (p. 178).

- How does she characterize the sisters’ relationships at this time?

- What textual evidence does she cite for her understanding?

- Read Rachel Havrelock’s comment on the sisters’ response in 31:14. How does her reading of this verse compare with Wendy Zierler’s.

- Read Genesis 31:17–21, in which Jacob and his family sneak away from Laban’s camp without informing him of their departure.

- There are two acts of deception in this section. What are they, who performs them, and who is on the receiving end of them?

- In Genesis 31:19–20, the account of Jacob’s departure is interrupted by a parenthetical comment about Rachel having stolen her father’s t’rafim. The translation renders this term as “household gods.” As the Central Commentary and Contemporary Reflection illustrate, commentators have debated the meaning of this term.

- What explanations of the t’rafim does Rachel Havrelock offer in her comment on 31:19?

- Read the section of Wendy Zierler’s Contemporary Reflection beginning with “What are these t’rafim...” (pp. 178–79). What interpretations of t’rafim have been given by traditional Jewish commentators and contemporary scholars?

- Read modern feminist biblical scholar J.E. Lapsley’s understanding of the t’rafim (p. 179). What does she believe the t’rafim represent to Rachel?

- Which of these explanations makes the most sense to you? Why?

- Read Genesis 31:25–32, in which Laban catches up to Jacob and his family and confronts Jacob for running away.

- What does Laban accuse Jacob of?

- How do Laban’s words in Genesis 31:26–30 compare to his daughters’ and son-in-law’s understanding of his actions in Genesis given their conversation in Genesis 31:1–16?

- Jacob swears an oath in response to Laban’s accusation of theft: “But the one with whom you find your gods shall not live” (Genesis 31:32).

- What in the text suggests that Jacob could be aware of the theft of the idols?

- Rachel Havrelock writes, “Jacob’s oath here is often cited by commentators as the reason for Rachel’s untimely death (35:18)” (p. 173). Wendy Zierler, however, disagrees with this interpretation in her Contemporary Reflection (p. 178).

- How would you compare Rachel Havrelock’s analysis of Rachel’s death with Wendy Zierler’s?

- Explain how the Rabbis connect Rachel’s theft with her early death in childbirth.

- Wendy Zierler reads the text closely to overturn this interpretation. What is her argument as to why the two events cannot be connected?

- Read Genesis 31:33–35, in which Rachel shrewdly keeps Laban from finding the t’rafim she stole and hid in her saddlebag.

- How does Rachel prevent Laban from finding his t’rafim?

- What does this tell you about the culture’s relationship to menstruating women?

- Wendy Zierler’s Contemporary Reflection (p. 179) cites modern feminist biblical scholar J.E. Lapsley, who says that the utterance, “the way of women is upon me” means that Rachel is “speaking two languages simultaneously.” In this reading, one statement has two meanings.

- What are the two possible meanings to Rachel’s statement?

- How does Lapsley believe Rachel turns the language of patriarchy against itself?

- Do you agree with Zierler that “Rachel thus emerges from this story as an archetypal feminist writer” (p. 179)? Why or why not?

- Read the poem “Rachel Solo” by Alicia Suskin Ostriker (p. 182).

- What reason does Ostriker provide as to why Rachel stole the t’rafim?

- How does this reason compare to those given in the Contemporary Reflection?

- How does this poem change or expand your reading of Rachel’s character?

CLOSING QUESTIONS

- What new insights into this parashah did you gain today?

- What new insights in general, did you gain from your study of Torah today?

- What questions remain unanswered?